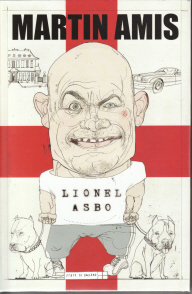

A bad book provides a variety of temptations, prime among them being just to ignore the thing and put it away in the Oxfam box. Bad books are usually written by incompetents, so are bad in uninteresting ways, but occasionally a real corker comes along: a poor or careless or contemptible piece of work by a highly rated author. Then the temptation is otherwise. The recent novel by Martin Amis, Lionel Asbo – State of England, is one such. (Cape, 2012, pp 276, ISBN: 978-0-224-09620, £18.99.)

I’m not interested in Amis or his life (although it does have a direct bearing on this novel), but I am much concerned with his writing ability. I’ve also asked myself why should anyone care about this novel? I can’t imagine the people who read this page would normally be bothered with it, but to me the subject of good and bad writing is always interesting. Lionel Asbo – State of England presents a unique example, because Amis has often declared himself to be in a class above his contemporaries. He once said that he “wrote the kind of sentences the other guys couldn’t write”, and is widely regarded as one of the more innovative and colourful users of the English language, a perception he accepts and enthusiastically reports.

Lionel Asbo – State of England is the story of a dysfunctional family of grown-ups in present-day London, the most prominent member of whom is Lionel, a sixth son. His five older brothers are called John, Paul, George, Ringo and Stuart. When Lionel’s mother ran out of Beatle names (apparently never having heard of Pete Best) she “christened” him Lionel. (Pete Asbo admittedly doesn’t have quite the same ring to it.) Lionel is now a brainless thug, in and out of prison for minor offences, usually offences of dishonesty or violence. At the age of 18 he changed his name to “Asbo”, the tag being seen as a badge of honour in his circle. Although he despises the lottery he accidentally gets hold of a winning ticket and collects £140 millions. He becomes a sort of celebrity yobbo, tasting the sweet life while staying much the same lovable old Lionel: he imbibes magnums of champagne and vast quantities of artisanal baked beans. (The latter are presumably baked beans made by craftsmen.) The protagonist of the novel is not, however, Lionel himself, but his nephew, one Desmond Pepperdine. Desmond, or Des, spends most of his young life in fear of Lionel uncovering his greatest secret: that as a teenager Des had enjoyed a physical affair with Lionel’s mother, Grace. (Lionel suspected someone else and bumped him off, but Des knows Lionel will find out the truth one day.) Towards the end of the novel Lionel duly takes his revenge.

Lionel Asbo – State of England is the story of a dysfunctional family of grown-ups in present-day London, the most prominent member of whom is Lionel, a sixth son. His five older brothers are called John, Paul, George, Ringo and Stuart. When Lionel’s mother ran out of Beatle names (apparently never having heard of Pete Best) she “christened” him Lionel. (Pete Asbo admittedly doesn’t have quite the same ring to it.) Lionel is now a brainless thug, in and out of prison for minor offences, usually offences of dishonesty or violence. At the age of 18 he changed his name to “Asbo”, the tag being seen as a badge of honour in his circle. Although he despises the lottery he accidentally gets hold of a winning ticket and collects £140 millions. He becomes a sort of celebrity yobbo, tasting the sweet life while staying much the same lovable old Lionel: he imbibes magnums of champagne and vast quantities of artisanal baked beans. (The latter are presumably baked beans made by craftsmen.) The protagonist of the novel is not, however, Lionel himself, but his nephew, one Desmond Pepperdine. Desmond, or Des, spends most of his young life in fear of Lionel uncovering his greatest secret: that as a teenager Des had enjoyed a physical affair with Lionel’s mother, Grace. (Lionel suspected someone else and bumped him off, but Des knows Lionel will find out the truth one day.) Towards the end of the novel Lionel duly takes his revenge.

Now then, let’s start unravelling some of this.

The title, which I have quoted in full until now, has a subtitle which is an indication of the author’s intent: this is a novel examining, or satirizing, or criticizing the “state” of modern England. Martin Amis has become an expatriate, so his visits to this country are short and intermittent. Distance can lend objectivity, but it can also introduce error. Much of what is wrong with this book can be traced, directly or indirectly, to Amis’s presumptuous stance, that he, a wealthy author from a privileged background and now living abroad, can tell us anything about the place we live in, through descriptions of a benefit-receiving or working-class family.

One of the many casual errors Amis commits concerns the “Asbo” – properly, it is an ASBO, an acronym for “Anti-Social Behaviour Order”, and crucially it was a civil order, not a criminal penalty. Amis should have known at the time he was writing that the ASBO, a mis-judged Blairite “fix” like so many others in those days, was largely unsuccessful in its results and was falling into disuse by the authorities. It was never a “badge of honour”, although the tabloid press thought it was – in reality most ASBOs were deployed against street drinkers, a hamfisted attempt to cure them of alcoholism.

Amis’s novel falls into two broad parts: the divider is Lionel’s lottery win, with his activities before and after spelled out. The first half is where most of the satirical work of the novel takes place, but Amis soon loses interest in that. The second half, a dazzling sequence of almost random social or pop-cultural references to foods, magazines, TV shows, music (not much, though, about texting, social networking, gaming, etc.), becomes increasingly like a farce. The repellent creation Lionel is now almost marginalized, and all Amis is left to write about is a world of scruffs and scroungers that he obviously dislikes and does not understand. The second half of the novel involves a constantly changing cast whose names, let alone their characters, are almost impossible to tell apart: Dawn, Dawnie, Des, Dudley, Daphne, Drago, Dylis? I suspected the author found himself late delivering his manuscript, and having done as much as he could with Lionel rushed something out so he could be rid of it. The closest literary parallel with these 100+ pages of frenetically recorded births and deaths and blow-out meals and posh houses and TV appearances and illnesses and infidelities are those old Confessions of … novels by Timothy Lea, but without the jokes. Not one.

Lionel Asbo is told in two main voices: a third-person narrative, which we should assume is intended as the authorial presence, and the dialogue, sometimes phonetically rendered (“Get you tits fixed” is a favourite line), of Lionel and his associates. The one time we see a letter written by Lionel, we are given a good look at his terrible spelling – for instance CUMPEW UH, with Amis obligingly providing the glottal stop. In fact, Amis frequently comments on the dialogue, explaining pronunciation, etc. At one point Lionel unexpectedly utters the long word “labyrinth”, and the author immediately points out that Lionel’s “enunciation” was improving: he was now saying labyrinf, not as might be expected, labyrimf. Later: “The first time he said brothel he pronounced it broffle, and the second time … he pronounced it brovvle.” As the book goes on there are more and more of these italicized interjections, to such an extent they become a sort of third narrative voice, jutting interchangeably into both the dialogue and the narrative. The two main voices are not even wholly discrete: the narrative style often slips into the vernacular, such as on p.93, in a description of Lionel’s suite of rooms in a snooty hotel in St James’s: “[There was a] bedroom, lounge, office area, bathroom with two sinks (and an extra shitter in a little closet of its own).”

In a 1990 Introduction to a reprint of William Sansom’s novel The Body, Anthony Burgess warns of the dangers that exist when there is a disparity between the mundane abilities and lifestyle of a novel’s characters and “the mentality of a professional writer who has read all the fiction and poetry ever written, especially in the modern age, and learned from their example how to contrive a highly original style of his own”. Burgess goes on to say that the danger is one of appearing to condescend. He discusses the way James Joyce enclosed Leopold Bloom “in a symbolism of great subtlety and erudition”, which elevated rather than condescended. He says that Sansom also avoids condescension. I think if Mr Burgess had known about Lionel Asbo he would have had a field day, as Amis not only keeps trying to show he is one of the lads, but consistently elevates condescension into class-based sarcasm.

It is the author’s mistakes that really set this novel out on its own. These range from the practical (poor research, or unfamiliarity with everyday life) to stylistic (bad writing).

On the practical mistakes, one hardly knows where to begin. Maybe you noticed that in the plot synopsis, Lionel’s mum christened him – no, she could only name him. Christening is a Christian sacrament. In 2006, according to Amis, milk was still being delivered in London in glass bottles – no, only a tiny handful of the posher addresses still receive any milk delivery at all, and an even tinier handful receive glass bottles, but Amis is probably protected from this knowledge. Des, a 15-year-old living in a rough urban neighbourhood, still attends school. Alone in the whole of London, this teenager wears short trousers, a purple blazer and he carries a satchel. He and Lionel live on the 33rd floor of a high-rise, where the lift never works, so they bravely run up and down the stairs, sometimes carrying furniture – I bet Martin Amis has never tried even to walk slowly up 33 floors. At one point, Lionel complains that his left pillock was aching – Amis obviously means his left testicle, or (daring slip into the vernacular) his left bollock, but “pillock” has only one meaning and that’s a stupid or annoying person. It’s from a Norwegian dialect word pillicock, which means penis. Diston (Amis’s imaginary inner-London slum area) is said to have gravid primary-schoolers – pregnant 5 to 10-year-olds?

Then Amis makes mistake after mistake when he talks about the crimes Lionel Asbo is said to have committed. Does this matter? Not really, but in a novel about the criminal underclass, where offences regularly feature, the one thing anyone can be sure of is that the perpetrators will know exactly what they’re up against and why they have been banged up. Lionel has form for “Extortion with Menaces” (doesn’t exist, and anyway Amis ought to be able to spot a tautology when he writes one), and “Receiving Stolen Property” (doesn’t exist – the offence is called Handling Stolen Goods, or just plain Handling). “Attempted Manslaughter” (p.18) is another non-existent offence in England and Wales – manslaughter is usually inadvertent, or is a reduction by mitigating circumstances from a murder attempt. There are several more Amis errors of this kind, too tediously technical to keep listing here, but all this sort of detail is quickly discoverable on the internet, as I just found.

However, it is on his home turf, writing the kind of sentences the other guys couldn’t write, that Amis is uniquely awful.

P.10: “Dawn simmered over the incredible edifice … of Avalon Tower.” How does that work? Simmering means cooking slowly just below boiling point; people can “simmer” with rage when they are holding it back. But a sunrise? (There is also an important character called Dawn … I wondered for a surreal moment if Amis was talking about her.)

P.22: “He squinted up with his unfallen eyes.”

P.28: “The worst stretch of Cuttle Canal was as active as a geyser: it spat and splatted, blowing thick-lipped kisses to the passers-by.” Presumably Amis is saying here that the canal is so damaged by pollution that it is in constant reaction, as chemical events take place. But “blowing thick-lipped kisses”?

P.34: “Diston, with its burping, magmatic canal, its fizzy low-rise pylons, its buzzing waste. Diston, a world of italics and exclamation marks.”

P.36: “… a heavy silence began to fuse and climb. A muscular, pumped-up, steroidal silence, a Lionel silence, shrill enough to smother the parched whispers of Jeff and Joe …” Difficult to see how any silence can “fuse” (i.e. unite or join or integrate), let alone “climb”. The “muscular, pumped-up, steroidal silence”, related to Lionel, is a flourish too far, especially as we know that Lionel is lazy, overweight and flabby. A “shrill” silence? A silence that can “smother” other sounds? (Jeff and Joe, incidentally, are two pit bulls, kept calm and domestic by being fed Tabasco every day. “Parched” is not the word for them.)

P.40: “… a film of water swam on the flagstones.” Presumably, Amis means a small puddle or a patch of water – “film” is generally used to describe a thin sheet or layer. But water is never in layers, and it never “swims”.

P.200: “They started forward, sliding sideways through the clenched teeth of the locked cars.”

P.245: “… the trail of life had frayed.”

Again, it becomes tedious to keep arguing this sort of detail – the above should serve fair warning to anyone who persists in thinking Amis is an inventive or descriptive or fluent writer. An earlier novel by Amis, the dreadful London Fields, had just as many similar solecisms. He gropes for images, he approximates descriptions, he uses the wrong words, but like a concert pianist hitting a dud note he plays it loudly, as if he meant it all along. The other guys, it is true, do not write like this – they are better at it.

Martin Amis once said (to Val Hennessy in Time Out), “My curse as a writer is that I am not read slowly enough. By reading my work fast one may perceive the local effects, the jokes, the virtuoso paragraphs but one gets absolutely no idea of the novel’s architecture or artistry.” Well, I read Lionel Asbo slowly, hoping for jokes, virtuosity and artistry, but it was a sordid experience. I wished I could have read this ill-judged and badly written novel faster.

Clearly, to quote another of his utterances, he needs frenzied editing by his publisher, and doesn’t get it. This interests me. One of my novels was published by Jonathan Cape (coincidentally at the same time as London Fields) and I was impressed by the thoroughness and sensitivity of the copy-editing, the attention to detail, the high standards on which the editorial staff insisted. I could hardly believe London Fields was from the same publisher. Yet dozens of these terrible Amisian gaffes still get through the Cape system somehow and I can’t help wondering how it happens. Perhaps his truculent style of surly ad hominem attack intimidates the editorial staff, so that he receives the lightest, most “respectful” treatment of his text? Or maybe he simply goes through the copy-edited text after Cape have finished with it, and restores his howlers?

The case of Martin Amis is not all that interesting when his work is considered in isolation, away from the white noise thrown out by his manner and his provocative and ill-informed public remarks about Islam, etc. He is a writer who was given a good start, but who peaked too early: Money: a suicide note (1984) is usually regarded as his best work, but that was three decades ago. His fiction since has been an up and down affair: sometimes no better than all right, sometimes awful. Lionel Asbo is his most recent fiction and it is at the bottom of his own mediocre scale. It reads like a terminal novel, a fizzling out of what some people thought all those years ago were the signs of a sparky new talent.

In year 2007, Prime Minister Gordon Brown requested members of the British public to suggest a four- or five-word slogan, perhaps in Latin, to sum up what signified modern Britain. I can’t remember if a winner was ever found, but a reader of The Times memorably suggested: Dipso Fatso Bingo Asbo Tesco. This witty remark said everything that Lionel Asbo says, but the novel is some 99,995 words longer and notably lacking in wit. I’d commend the slogan to Martin Amis, but I rather suspect he wouldn’t know what a “tesco” is.