We are now only a few weeks away from the release of my next novel The Adjacent (to be published by Gollancz on 20th June), so it’s time to mention a debt. The background for a section of the book came from the RAF bombing campaign against Germany in the Second World War. This is the second of my novels to deal with this difficult period of British history: The Separation (2002) described more directly the impact on the life of a young man who flew with Bomber Command in the early part of the war. The Adjacent does not go over similar ground, but it does touch on the same sensitive subject.

In June 2012 a permanent memorial was created to the RAF Bomber Command campaign of the second world war. The memorial is to all lives lost during the war, notably the estimated 600,000 civilians and non-combatants killed on the ground by the bombing, but it is also, at last, a memorial to the young men, all volunteers, who served as aircrew in the air force. Theirs was one of the most dangerous jobs of the war. 55,573 RAF men were killed in bombing raids during the war, and another 18,000 were wounded or taken prisoner – which was more than half the total number of crew involved (about 120,000). Serving in an RAF bomber gave a worse chance of non-survival than that of an infantry officer in the 1914-18 war. Bomber Command survivors and the families of many of the lost men have campaigned for years for the sacrifice of so many lives to be acknowledged.

In June 2012 a permanent memorial was created to the RAF Bomber Command campaign of the second world war. The memorial is to all lives lost during the war, notably the estimated 600,000 civilians and non-combatants killed on the ground by the bombing, but it is also, at last, a memorial to the young men, all volunteers, who served as aircrew in the air force. Theirs was one of the most dangerous jobs of the war. 55,573 RAF men were killed in bombing raids during the war, and another 18,000 were wounded or taken prisoner – which was more than half the total number of crew involved (about 120,000). Serving in an RAF bomber gave a worse chance of non-survival than that of an infantry officer in the 1914-18 war. Bomber Command survivors and the families of many of the lost men have campaigned for years for the sacrifice of so many lives to be acknowledged.  Winston Churchill, who through much of the war was an enthusiastic advocate of destroying German cities, and killing as many civilians as possible, changed his mind towards the end of the war, probably realizing belatedly how history might regard him. Under his orders, no Bomber Command campaign medal was ever struck, surviving career officers were demoted to their pre-war ranks, and most of the remaining civilian volunteers were demobilized and sent home as soon as possible.

Winston Churchill, who through much of the war was an enthusiastic advocate of destroying German cities, and killing as many civilians as possible, changed his mind towards the end of the war, probably realizing belatedly how history might regard him. Under his orders, no Bomber Command campaign medal was ever struck, surviving career officers were demoted to their pre-war ranks, and most of the remaining civilian volunteers were demobilized and sent home as soon as possible.

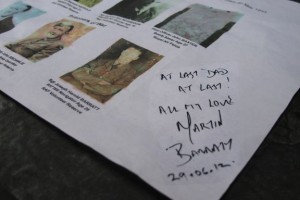

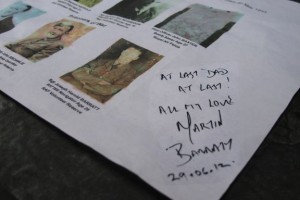

The  memorial is situated in Green Park, London, at the Hyde Park Corner end of Piccadilly. It contains some suitable statuary of an RAF crew, and several commemorative tablets explaining what was at stake for the ordinary people who were so terribly affected by this aspect of the war. I found it to be an unpretentious monument, and was moved by the many simple and heartfelt comments people had written on their cards and tributes.

memorial is situated in Green Park, London, at the Hyde Park Corner end of Piccadilly. It contains some suitable statuary of an RAF crew, and several commemorative tablets explaining what was at stake for the ordinary people who were so terribly affected by this aspect of the war. I found it to be an unpretentious monument, and was moved by the many simple and heartfelt comments people had written on their cards and tributes.

Because none of my family or close friends were involved in RAF activities during WW2, and because I am a novelist and not an historian, I’ve always felt a bit uncomfortable with the idea of my taking a stand on the morality or otherwise of the bombing of Germany. However, I have been reading books about this subject ever since I was a teenager, invariably torn between horror of what happened and sympathy for those caught up in it.

I have long held that many of the books written by participants in WW2 are the literary equivalent of the outpouring of poetry that appeared in the First World War. In fact, relatively little good poetry was produced in 1939-45 (Daniel Swift’s recent book Bomber County, 2010, is the best existing account of what we have — reviewed by me here), but in the immediate postwar years, starting in the late 1940s but mostly from about 1950 onwards, there was a veritable flood of books containing war stories, war memoirs, war experiences: captives escaping from prisoner-of-war camps, agents parachuted behind enemy lines, bombers attacking dams in the Ruhr, nurses and firemen in the Blitz, gunners in the rear turret of Lancaster bombers, U-boat submariners in the North Atlantic, memoirs of generals, and so on. At first, during the 1950s, these books were produced by trade publishers as general titles, but in recent years those that are reprinted come from specialist military publishers, small presses or have been sponsored by the families. Many can be found in the Military History sections of large bookstores (which like many bookshop departments can be a bit of a misleading label), and of course the internet will locate most of them. They make up a neglected but unique vernacular history of that appalling war. None of them is a literary masterpiece, but like much of the poetry from the earlier war they are written with energy and a sense of total personal experience and commitment, they are moving, they contain material that is sometimes graphic or shocking or surprising, they are above all true in every sense of the word. Here are a few, but there are literally hundreds more:

Bomber Pilot, Leonard Cheshire (1943)

The Wooden Horse, Eric Williams (1949)

A WAAF in Bomber Command, Pip Beck (1989)

No Moon Tonight, Don Charlwood (1956)

The Naked Island, Russell Braddon (1952)

P.Q.17, Godfrey Winn (1947)

A postscript. I visited the Bomber Command memorial at the end of June 2012, just two days after it had been officially opened by the Queen. Many of the floral tributes and cards were still fresh. I found the one from Martin Barratt (in the photograph above, dated the day before), and took a couple of pictures of it. The poignant little message struck me as sharing the same sense of ordinary decency and pain that I had encountered many times before in these books. I moved away, looking at the other tributes. When I returned to the place where Mr Barratt’s message had been left, I discovered that it was now missing. It had not been moved to one side, it had not fallen to the floor, there was not enough of a wind to have blown it away. I looked everywhere around, but someone must have removed it. I can’t imagine why.