‘Cooting’ is a slang word describing a transgressive sexual act. I had never come across it before, either the word or the act, but I discovered the meaning (as no doubt you will too, after you read this) in the online Urban Dictionary. I don’t want to repeat the definition here. It is beyond question thoroughly disgusting.

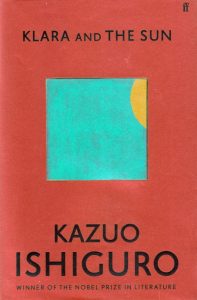

You might well wonder why I was even looking it up. I came across the word in Kazuo Ishiguro’s new novel, Klara and the Sun.

The book includes a description of a large and noisy machine that does road work. It is coloured a dirty pale yellow and through its three funnels it emits an acrid black smoke cloud, so dense and polluting that it obscures the light from the sun. The narrator (of whom more in a moment, but for now it’s enough to say the narrator is a solar-powered AI hominoid) sees this as a symbolically destructive machine and becomes determined to destroy it. The word Cootings is painted on its side.

Later in the book, the hominoid learns of a way to damage what is now called the Cootings Machine: if a certain fluid, referred to in Ishiguro’s mumbo-jumbo as a P-E-G Nine solution, is introduced into the workings the machinery would be made useless. As it happens, P-E-G Nine solution is present inside the hominoid, in ‘a small cavity … at the back of the head, where it meets the neck’. With the help of a human friend, the AI hominoid suffers a minor incision with a handy screwdriver, and the P-E-G Nine solution is introduced into the workings. The Cootings Machine is duly disabled.

This combination of a criminal act with body horror and body fluids made me wonder what on earth the author was getting at. It seemed dark and mysterious symbolism might be going on.

And why is it called Cootings? Cootings is apparently the name of the machine’s manufacturer. As the book is set in a slightly futuristic version of our own world, wouldn’t heavy industrial machinery of this sort be more realistically likely to have JCB or Kobelco or Massey-Ferguson painted on its side? Why make up a new name? Kazuo Ishiguro is self-consciously a serious writer at the top of the literary ladder: he is the author many novels, the winner of multiple book prizes, and is now a Nobel Laureate. The choice of this name must have been an informed, deliberate one, and this is why I went in search of the meaning of the word. When I learnt the definition given by the Urban Dictionary, I thought for a fleeting moment that I had stumbled on and opened up a whole new and stunningly original depth of dark symbolism. While the fleeting moment persisted I was shocked and daunted by the writer’s audacity.

Well, not really. The Cootings Machine turns out to be a minor sub-plot, the threat it presents is exaggerated by the narrator’s unworldly inexperience, and the attack on it with P-E-G Nine solution is carried out off-stage. And because it turns out there is more than one Cootings Machine in existence, to damage one of them is ultimately pointless. It is barely referred to again.

This is a risk of seeming to labour a point, but in fact it is one small but clear example of the many superficial and inconsequential images that litter this novel. Ishiguro clearly had no more idea than me or anyone else reading this what ‘cooting’ meant. Presumably he thought he was making it up. Presumably he didn’t think to spend ten seconds Googling the word (as I did earlier today) just in case it was slang for a disgusting and transgressive sexual act, just in case he wanted to think again and perhaps call it JCB Machine instead.

The book is narrated by Klara, an ‘Artificial Friend’ designed to help girl teenagers through their difficult years. Klara is referred to as a robot at one point, presumably because she has been fashioned in a human-like, i.e. hominoid, shape, with legs, a torso, a face and hair. She wears clothes, and goes to her own room at night. She is female in some undescribed fashion, so presumably male hominoids are made male in some other fashion. (If so, with what dark and mysterious reason?)

One groans at the familiarity, as one did in McEwan’s not dissimilar novel in 2019, Machines Like Me, but also at the impracticality and the sheer old-fashionedness of the idea. Walking and talking humanoids, from Robbie the Robot to Marvin the Paranoid Android, have used up the notion: they now amply fulfil the condition of intellectual decadence, as set out by Joanna Russ in her magisterial essay in 1971, ‘The Wearing Out of Genre Materials’. Modern AI is genuinely a much more subtle thing, from the supermarket till that offers you money off next time you buy the chocolate biscuits you enjoy so much, to the intrusive data harvesting of social media engines, and to the hostile regimes who try to influence the results of elections. A walking, wondering, blank-eyed doll who calls a smartphone an ‘oblong’ and who thinks houses are painted in different colours so the residents will not enter the wrong one by mistake, is nowhere close to that league. Not AI at all, then. Better as AS?

Klara is our narrator for the full length of the 80,000-odd words, so we are forced to see the world through her restricted and estranged perception. Some critics call this the use of an unreliable narrator, but that is a much more sensitive and sophisticated literary device. Klara is not unreliable: she simply doesn’t get it. The matters she doesn’t get are left to us to try to understand, as it were, on her behalf. It is dull and sometimes maddening having to go through page after page, mentally interpreting for a clod. It distances the reader not only from the action and the world in which it takes place, but more importantly from the characters. They are third-person ciphers, respectively referred to as ‘Manager’ (of the obsolete type of department store where Klara sits in a sales window), or ‘the Mother’ (of Josie, the teenage girl who is being artificially befriended), or ‘Mr Paul’ (father of same). In dialogue, Klara habitually addresses them by these second-person labels.

All this is bad enough, but Ishiguro adapts his style to the purpose. His English is bland, careful, circumlocutory, slightly grandiloquent, always shrinking from commitment to his characters or his subject. One is often reminded of Stevens, the clod of a butler in The Remains of the Day, 1989, who behaved like a stooge servant in a TV costume drama, following the pedantic script and missing all the hints of a real world around him. Much of the dialogue in Klara and the Sun is repeated, the characters treating each other as people who haven’t listened or understood, or who defer to each other.

As for the lack of commitment, Ishiguro is depicting a future world in which the geneticists and eugenicists have perfected the art of super-selection, in which the bright kids are ‘lifted’, given good health and schooling and higher education, plus an easy passage into the chattering classes, while the dullards are fascistically consigned to pauperdom or death. Does Ishiguro give any hint of the moral horror of such a world? No – he shrinks from that, just as he and Stevens shrank from the appeasement of the Nazi sympathizers in the big country house of Remains of the Day.

A novelist should approach a fantastic or speculative element with a full-on open mind, aware of the consequences of technological inventions, of the implicit warnings contained in social extrapolation, of the good or bad example a postulated future might set, of the impact on the people who are involved. It is not enough to watch a few sci-fi films on Netflix, or pick up futuristic-seeming slang from comics. The fantastic is a powerful and important literary strand, largely ignored or patronized or misunderstood by the literary world at large, but the best examples of fantastic literature treat their material with seriousness, responsibility and imagination. A secondrate imagining of these things leads to secondrate literature. Klara doesn’t get it, but neither does Kazuo Ishiguro.

Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro. Published by Faber & Faber, £20.00, ISBN: 978-0-571-36487-9

The book is largely about the liminal and always slightly disconcerting experience of passing through an airport. All travellers are familiar with the fact that every airport has two ‘sides’. In landside we check to see if the flight is on time, or when it is likely to board. If we are arriving from a flight, landside is where we are able to pick up our luggage. Most of us don’t delay long in landside. Coming in we are anxious to get home. On an outward journey we hasten towards:

The book is largely about the liminal and always slightly disconcerting experience of passing through an airport. All travellers are familiar with the fact that every airport has two ‘sides’. In landside we check to see if the flight is on time, or when it is likely to board. If we are arriving from a flight, landside is where we are able to pick up our luggage. Most of us don’t delay long in landside. Coming in we are anxious to get home. On an outward journey we hasten towards: Last year I wrote an introduction to a new American edition of John Fowles’s novel The Magus. The book has just been announced by Suntup Editions in California. This astonishing novel, first published in 1965, has not been available in hardcover for several years.

Last year I wrote an introduction to a new American edition of John Fowles’s novel The Magus. The book has just been announced by Suntup Editions in California. This astonishing novel, first published in 1965, has not been available in hardcover for several years. Long-term friend Bill Seabrook has written to say that yesterday (which was publication day for Expect Me Tomorrow) he received an email from Amazon, concerning his pre-order for the book.

Long-term friend Bill Seabrook has written to say that yesterday (which was publication day for Expect Me Tomorrow) he received an email from Amazon, concerning his pre-order for the book. The Glasgow Film Theatre is running a short season of Nolan films on various dates during July, starting on 3rd July with a late-afternoon 35mm screening of The Prestige. On 5th July I will be at the GFT to introduce a second screening at 8.00pm, followed by a short Q&A.

The Glasgow Film Theatre is running a short season of Nolan films on various dates during July, starting on 3rd July with a late-afternoon 35mm screening of The Prestige. On 5th July I will be at the GFT to introduce a second screening at 8.00pm, followed by a short Q&A.  We hav

We hav But more than this. Like many writers we have built up a huge number of spare copies of our own books. The other day we delivered six heavy boxes of these copies to Thistle Books in Glasgow. The copies are both hardcover and paperback, all of them are new and unread, most are first editions or first printings, and we signed every copy. Included are several copies of the now rare first edition of The Glamour, as well as more recent titles. (We threw in a handful of surprise inclusions in some of the copies.) Nina also donated most of her own titles.

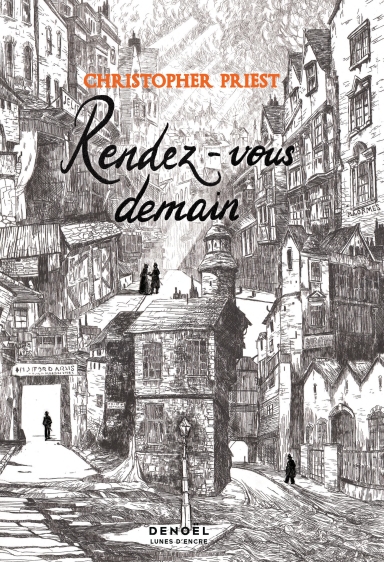

But more than this. Like many writers we have built up a huge number of spare copies of our own books. The other day we delivered six heavy boxes of these copies to Thistle Books in Glasgow. The copies are both hardcover and paperback, all of them are new and unread, most are first editions or first printings, and we signed every copy. Included are several copies of the now rare first edition of The Glamour, as well as more recent titles. (We threw in a handful of surprise inclusions in some of the copies.) Nina also donated most of her own titles. Here is the cover for my next novel, to be published by Denoël in Paris, in April 2022. The title in English is Expect Me Tomorrow.

Here is the cover for my next novel, to be published by Denoël in Paris, in April 2022. The title in English is Expect Me Tomorrow. I am arranging for a copy to be made available for showing at Novacon. This takes place between 12th and 14th November this year, at the Palace Hotel, in Buxton. I shall be there. Here is

I am arranging for a copy to be made available for showing at Novacon. This takes place between 12th and 14th November this year, at the Palace Hotel, in Buxton. I shall be there. Here is

The film was of course based on my own novel. It was directed by Christopher Nolan – at that time he was not the major Hollywood director he is now perceived to be. I took a special interest in the process of transition from book to film for reasons which should be obvious. I had little to do with the actual mechanics of the production, but being a witness to a lot of bemusing activity happening over there in far California was intriguing enough. The process of adaptation appealed to me as a craft matter: I knew better than anyone what a complex and cerebral book it was, and when I heard that a film was in preparation I started wondering how on Earth anyone could make anything coherent from it. When I was able to see the finished product the answer was a welcome and rather satisfying surprise.

The film was of course based on my own novel. It was directed by Christopher Nolan – at that time he was not the major Hollywood director he is now perceived to be. I took a special interest in the process of transition from book to film for reasons which should be obvious. I had little to do with the actual mechanics of the production, but being a witness to a lot of bemusing activity happening over there in far California was intriguing enough. The process of adaptation appealed to me as a craft matter: I knew better than anyone what a complex and cerebral book it was, and when I heard that a film was in preparation I started wondering how on Earth anyone could make anything coherent from it. When I was able to see the finished product the answer was a welcome and rather satisfying surprise.

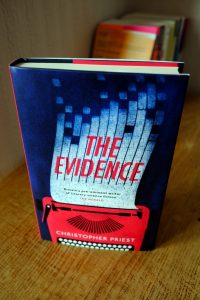

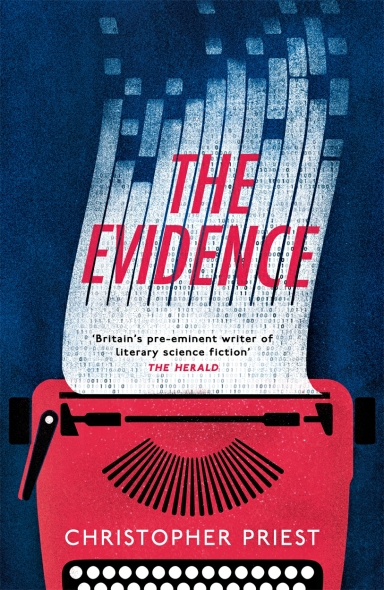

First copies of The Evidence arrived this morning, looking good. I was very pleased to see this in print at last, after what turned out to be a fairly normal process, attended distractingly and worryingly by the social upheaval and feelings of uncertainty known to everyone. Books endure, books are a constant.

First copies of The Evidence arrived this morning, looking good. I was very pleased to see this in print at last, after what turned out to be a fairly normal process, attended distractingly and worryingly by the social upheaval and feelings of uncertainty known to everyone. Books endure, books are a constant. and says Gardners are supplying from stock. They will have copies tomorrow. Independent bookshops remain the best place to buy new books.

and says Gardners are supplying from stock. They will have copies tomorrow. Independent bookshops remain the best place to buy new books. This is the Brexit Biscuit, a shortbread snack of two halves. It may be eaten whole, or one half at a time, or simply broken apart in a symbolic way: one side kept forever, the other discarded. It comes in a pack of twelve, wrapped in a free but tear-up-able copy of Article 50, and packed in a beautiful old-fashioned tin box, good for keeping things in. Obtainable

This is the Brexit Biscuit, a shortbread snack of two halves. It may be eaten whole, or one half at a time, or simply broken apart in a symbolic way: one side kept forever, the other discarded. It comes in a pack of twelve, wrapped in a free but tear-up-able copy of Article 50, and packed in a beautiful old-fashioned tin box, good for keeping things in. Obtainable  My novel

My novel  Although characterized in some quarters as me ‘slamming’ Mr Nolan (which no doubt will be said again after the interview has been read), the book is in fact an appreciative and nuanced study of how a serious and complex feature film is conceived and made by a young film maker at his peak.

Although characterized in some quarters as me ‘slamming’ Mr Nolan (which no doubt will be said again after the interview has been read), the book is in fact an appreciative and nuanced study of how a serious and complex feature film is conceived and made by a young film maker at his peak. There is no mention in it anywhere of lockdown, virus or pandemic. There are no jokes about eyesight tests, no plague ships polluting the oceans, no face masks. It describes a place where crime no longer exists, and in which three murders have to be investigated.

There is no mention in it anywhere of lockdown, virus or pandemic. There are no jokes about eyesight tests, no plague ships polluting the oceans, no face masks. It describes a place where crime no longer exists, and in which three murders have to be investigated. There are approximately sixty luxury cruise liners in current operation with a deadweight greater than 120,000 tonnes. Another forty-two such ships are currently on order, or under construction.

There are approximately sixty luxury cruise liners in current operation with a deadweight greater than 120,000 tonnes. Another forty-two such ships are currently on order, or under construction.

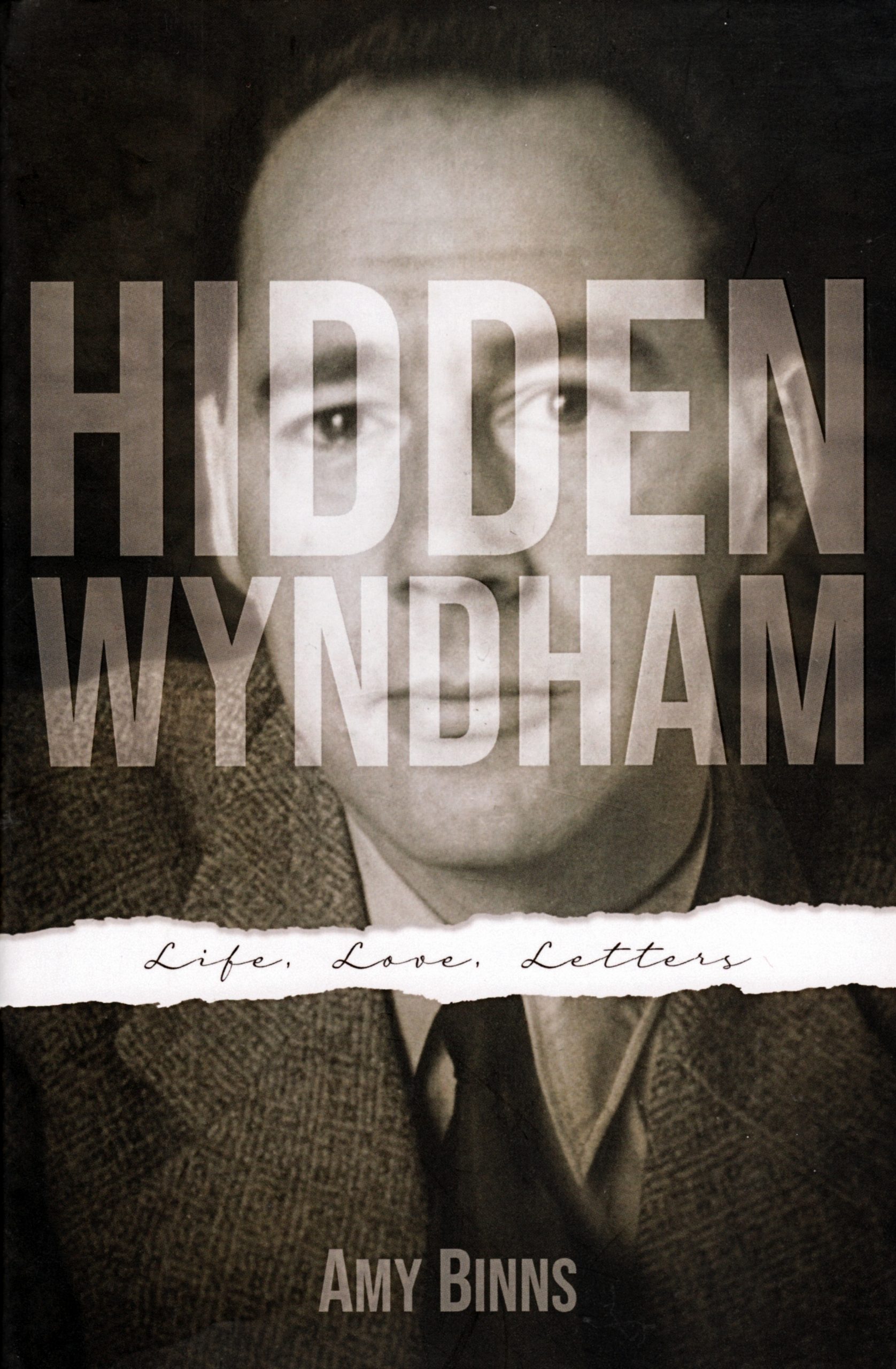

At last we have in Amy Binns’s new biography of John Wyndham a well-written and objectively researched book, half a century after his death in 1969. Wyndham was the first successful modern science fiction writer to emerge in Britain since H G Wells. His work, mostly written in the late 1940s or early 1950s, has acquired period charm, and some of the dialogue is middle class in tone and dated in style, but there is a hardness of vision, a satirical edge, a sense of the author’s regrets and sometimes amusement about the follies of the world at large.

At last we have in Amy Binns’s new biography of John Wyndham a well-written and objectively researched book, half a century after his death in 1969. Wyndham was the first successful modern science fiction writer to emerge in Britain since H G Wells. His work, mostly written in the late 1940s or early 1950s, has acquired period charm, and some of the dialogue is middle class in tone and dated in style, but there is a hardness of vision, a satirical edge, a sense of the author’s regrets and sometimes amusement about the follies of the world at large. Three years ago, along with a lot of other people in Britain, I placed my vote in the European referendum. The next morning I woke up to discover that overnight I had been labelled a “Remainer”, and was informed that my vote was on the losing side and that I therefore no longer had a voice in what would happen as a result of the referendum. All that has continued to be true ever since.

Three years ago, along with a lot of other people in Britain, I placed my vote in the European referendum. The next morning I woke up to discover that overnight I had been labelled a “Remainer”, and was informed that my vote was on the losing side and that I therefore no longer had a voice in what would happen as a result of the referendum. All that has continued to be true ever since.