At last we have in Amy Binns’s new biography of John Wyndham a well-written and objectively researched book, half a century after his death in 1969. Wyndham was the first successful modern science fiction writer to emerge in Britain since H G Wells. His work, mostly written in the late 1940s or early 1950s, has acquired period charm, and some of the dialogue is middle class in tone and dated in style, but there is a hardness of vision, a satirical edge, a sense of the author’s regrets and sometimes amusement about the follies of the world at large.

At last we have in Amy Binns’s new biography of John Wyndham a well-written and objectively researched book, half a century after his death in 1969. Wyndham was the first successful modern science fiction writer to emerge in Britain since H G Wells. His work, mostly written in the late 1940s or early 1950s, has acquired period charm, and some of the dialogue is middle class in tone and dated in style, but there is a hardness of vision, a satirical edge, a sense of the author’s regrets and sometimes amusement about the follies of the world at large.

His books and short stories are remarkable for their constant depiction of strong, decisive or capable women. His speculative ideas, although sometimes reworked from his own early stories or from the generality of the genre, were presented plausibly and with a nice sense of menace. For example, his second novel, The Kraken Wakes, created a genuine and growing feeling of mystery and unease while an invasion force went about a deliberate and unexplained process of destroying our planet.

Amy Binns’s excellent book, Hidden Wyndham, depicts the author as a shy, withdrawn and deeply private man. There are no shocking details to be excavated from the past, there is no scandal, no secret life, although a tinge of sadness hung around him. At first he had to deal with the effects of being born into a dysfunctional middle-class family, his mother a distant if loving presence, his father a ne’er-do-well lawyer who sponged constantly off his wife’s wealthy parents. As a young man Wyndham began a tentative writing career in the American pulp magazines, which was interrupted when the second world war began. After war service he returned to his writing and became unexpectedly a major publishing phenomenon.

When his first books were successful he became known to other science fiction writers in London, including Arthur C Clarke (then much less celebrated), William F Temple and John Christopher. Wyndham regularly attended their monthly meetings at the White Hart and Globe pubs, but they seem to have learned little or nothing about his life. Later he collaborated with them to launch the magazine New Worlds SF as a commercial venture, but he retained his privacy. He lived somewhere in London, but they had no idea where. When he signed the official papers as Chairman of the new company, his address was revealed to be at a members’ club they had never heard of. ‘Wyndham’ was a kind of pseudonym – his real name turned out to be John Wyndham Parkes Lucas Beynon Harris.

When in 1963 he announced that he had married a friend called Grace Wilson, with whom he had been close for more than two decades, the other writers were astonished: he had always seemed isolated, self-sufficient, closed off, a classic bachelor of choice. In fact, as we discover from the archive of his hundreds of letters written to Grace (many of them sent while he was serving in the Army after D-Day), theirs was a loving, intimate and trusting relationship. For most of that time they chose to present as just friends: they rented adjacent rooms in London’s Penn Club, a strictly run private club established by Quakers which would not condone extra-marital relationships. Because marriage, or even more the admission of an affair, would in those days have had a drastic impact on Grace’s professional career (she was a senior teacher at a girls’ school, and for years the main breadwinner of the two of them), they decided to stay unwed. John Wyndham himself was content not to formalize their relationship until late in life. Once married, he and Grace stayed happily together until Wyndham died. He was at ease for the rest of his life, and the books brought him substantial financial security.

The quality of his work takes the general form of a bell curve. His early contributions to American science fiction magazines were typical of the period and have become badly dated – many of them were reprinted in modern editions after his success, and are mainly of curiosity interest now. The war arrived and Wyndham had to stop writing. He became one of the generation of British writers whose careers were put on hold for several years: others include Elizabeth Bowen, William Sansom, Rex Warner, H E Bates, Graham Greene. The involuntary pause had a different impact on the work of each individual, but in Wyndham’s case it seems to have been the making of him. The Day of the Triffids (1951), the first book published as by John Wyndham, is skilfully told in a mature and readable style. His other three great novels followed: The Kraken Wakes (1953), The Chrysalids (1955) and The Midwich Cuckoos (1957).

But these four represent the peak, the upper limit of the bell curve. Four more novels followed, none of them at the same standard as his best. Trouble with Lichen (1960) was a social satire, a distinct lowering of temperature from the others. The Outward Urge (1959, published in collaboration with ‘Lucas Parkes’ as nonexistent science adviser) was another disappointment. The last novel to be published in his lifetime was Chocky (1968), which was an adult novel with a child as a main character. After his death, a novel he had been struggling with for several years was finally published. Web (1979) was a long way below par, something of which John Wyndham himself was almost certainly aware.

Forty years after Wyndham’s death, an unpublished novel called Plan for Chaos was found in his papers at University of Liverpool. After a university press hardcover appeared in 2009, Penguin later published it in paperback. (I was commissioned to write an Introduction to their edition.) For imagined commercial reasons Plan for Chaos had been aimed at the American market, but the attempts at American dialogue and slang were crude and unsuccessful through most of the opening chapters. The second half of the novel is much better, and the story of the Nazi scientists who escaped to South America, and aimed to take over the world in their flying saucers, at least has the familiar Wyndham ironic humour.

Interestingly, Plan for Chaos was written after The Day of the Triffids, but it is significantly less accomplished. In correspondence with Frederik Pohl, his American literary agent, Wyndham said he thought the Englishness of Triffids would make it difficult to sell in the States. He put the better novel aside while he wrote the much weaker book intended to replace it.

There is some evidence (noted by Dr Binns in her book) that Ira Levin and John Wyndham had corresponded, and that Levin was likely to have read Plan for Chaos in manuscript. His own novel, The Boys from Brazil (1976), has a remarkably similar plot in outline. One of his other novels, This Perfect Day (1970), contains a coded acknowledgement to Wyndham.

The mysteries of John Wyndham’s private life turn out to be trivial, and no one’s business but his own. To read his love letters to Grace feels intrusive, but they give a context to the body of his best work. He seemed diffident and aloof to some who met him, but Amy Binns reveals him as a decent and faithful man, a lover of the countryside and a gifted storyteller. His books have been continuously in print for nearly seventy years, an extraordinary achievement.

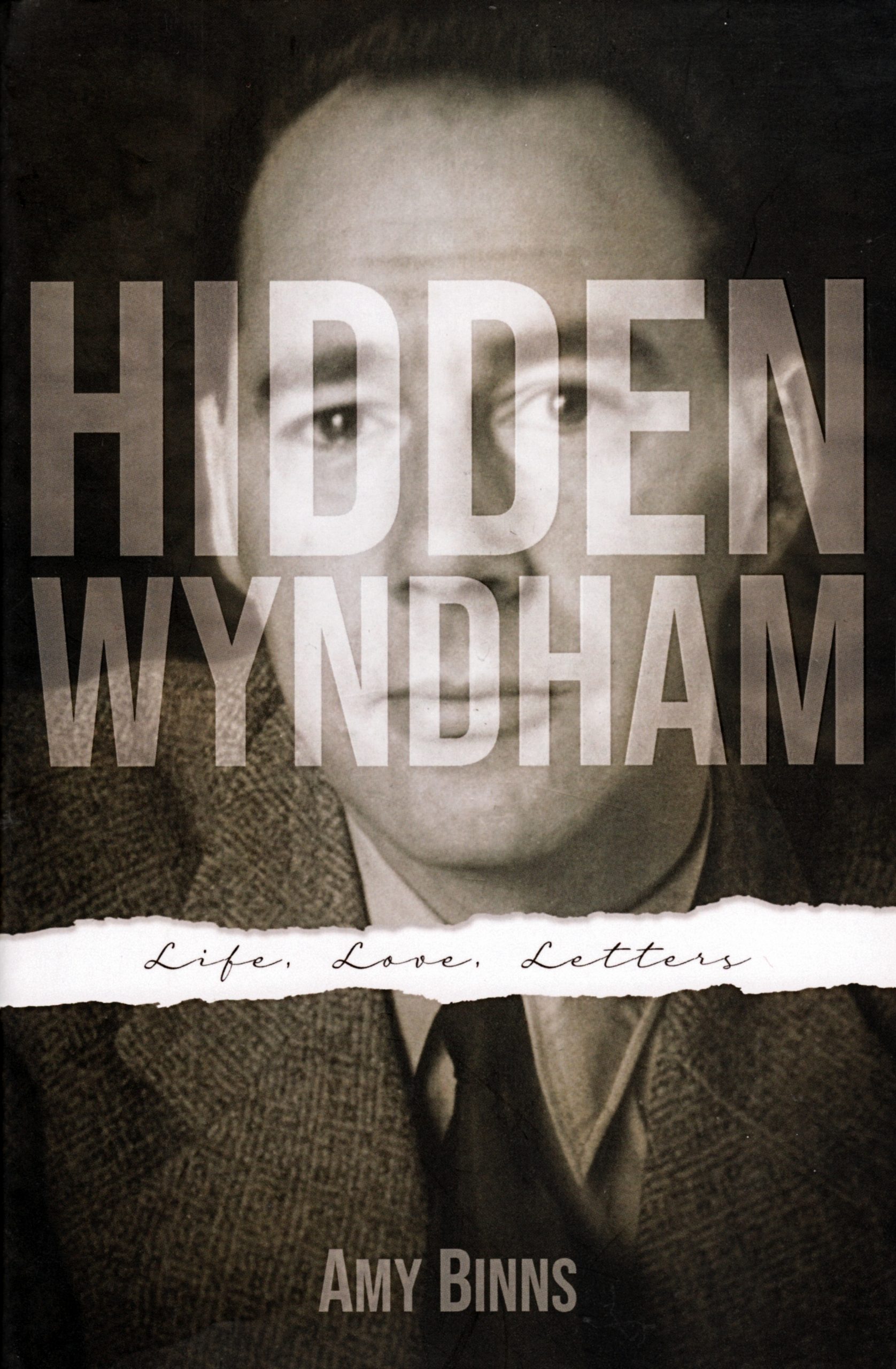

Hidden Wyndham — Life, Love, Letters by Amy Binns, Grace Judson Press, pp 288, £10.95. ISBN: 978-0-9927567-1-0