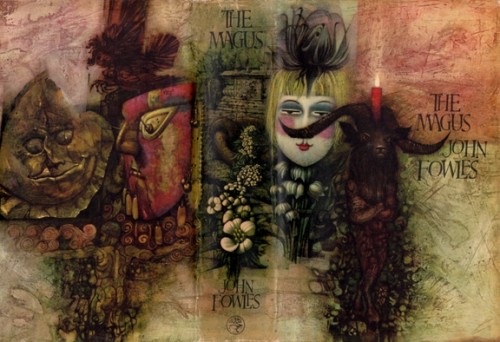

My Christmas present to myself was a copy of John Fowles’s novel The Magus, which I re-read over the holiday period. The copy was a well-preserved UK first edition, which I bought not all that expensively from the Fowlesian specialist book dealer: Magusbooks, run by Bob Goosmann in Sacramento. Mr Goosmann also manages the best website on Fowles, with a mass of biographical and bibliographical detail, background information on Fowles, many photographs, and much interesting trivia (such as a translation from the Latin of the last line of The Magus). The website is here, and has direct links to the bookstore.

The first copy I owned of The Magus was a paperback urged on me in 1970 by my friend Graham Hall. The cover had been torn off because it carried a photograph of the actor Michael Caine, whom Graham loathed. (John Fowles disliked him too, as I discovered many years later). Caine was the star of the 1968 film adaptation of the novel (a pretty terrible film, with a badly chosen cast). Both the film and the novel had passed me by and I had no strong feelings about Michael Caine, but it meant that when I read the book, which came into my hands lacking a blurb and descriptive text of any kind, I had no idea what was in store. Once I had started reading, The Magus glued me to a chair for an entire weekend and overall had a profound impact on me, both as a reader and as a young writer.

The first copy I owned of The Magus was a paperback urged on me in 1970 by my friend Graham Hall. The cover had been torn off because it carried a photograph of the actor Michael Caine, whom Graham loathed. (John Fowles disliked him too, as I discovered many years later). Caine was the star of the 1968 film adaptation of the novel (a pretty terrible film, with a badly chosen cast). Both the film and the novel had passed me by and I had no strong feelings about Michael Caine, but it meant that when I read the book, which came into my hands lacking a blurb and descriptive text of any kind, I had no idea what was in store. Once I had started reading, The Magus glued me to a chair for an entire weekend and overall had a profound impact on me, both as a reader and as a young writer.

Four decades and several re-readings later I’m still convinced it is one of the finest and most influential novels of the last century. The writing is beautiful, in particular in the long descriptive scenes in the first fifty pages or so (the physical descriptions throughout the long novel are executed with precision, delicate language and a vivid visual flair). Much of the story is told through scenes of dialogue, and these are handled plausibly and with a real sense of place, nuance and character.

The story is gripping. In the autumn of 1952 a young English teacher takes up a position at a private school on a small Greek island. By the following summer the schoolmaster, one Nicholas Urfe, has become trapped in an existential cabal conducted by an elderly man called Conchis, who lives on the island in a luxurious villa on the south coast. Urfe’s relationship with Conchis becomes a sort of masque, a ritualistic psychodrama overseen by the self-styled mystic, for which Urfe has apparently been chosen at random. The narrative tells how Urfe is drawn into the conspiracy, how he becomes deeply entangled and what happens when he finally escapes. The plot of the novel is complex, constantly surprising the reader. Towards the end of the book, as Urfe tries to unravel the mystery that has been woven around him, the story takes on the aspect of a thriller, with one revelation after another, opening up the story not to explanation but to a deeper realization of the complexity of the conspiracy. At the end of the novel, the famous final sequence complete with its obscure Latin tag, nothing is clear or resolved in terms of practical explanation, but philosophically both the reader and the central character have moved to a different plane of understanding. It is a choice example of how an undefined or ambiguous ending to a novel places a memorable charge on the reader.

No novel is ever perfect, though, and The Magus has its imperfections. As the years go by they seem more and more problematical, partly because the novel is not yet so old that we can make excuses for it (in the way we tolerate the sexual coyness of novels from the 19th and early 20th centuries, for instance), and partly because Fowles himself was living and working in the modern age. Fowles published the original version of The Magus in 1966, and in 1977 published a fully reworked and revised version. (It was the 1977 edition I re-read last week, incidentally, not my newly acquired first edition.) Fowles should certainly have known by 1977 that sensibilities were changing. His sexualized depiction of two of the young women in the novel (they are in their early 20s, but he usually refers to them as ‘girls’) will offend some people today, as will, and much more acutely, the characterization, description and role of the (alleged) American academic Joseph Harrison.

John Fowles, who died in 2005, is of course not around to defend himself, but he might well argue that the attitudes and mores of the novel accurately reflect those of its period, the early 1950s. However, because the book was published thirteen (and twenty-four) years after its period it is technically an historical novel, a genre which usefully deploys modern sensibility in an ironic or detached way to comment subtly on the past. There is little irony or detachment of this particular social kind in The Magus.

The other problem lies in the long central section of the novel, during which Nicholas Urfe is bemused by the intricacies of the plot that surrounds him. He is constantly questioning his own take on reality. Is this mysterious old man telling him the truth or is everything a fabrication? Have these alluring young women been employed as actors, as he is told, or is a more subtle temptation being put before him? Why are people walking around in masks from Greek mythology? Are those really Wehrmacht soldiers operating in the hills of the island, or are they actors too? Is he free to leave, or is he somehow a captive? And so on. This entire sequence continues to be written in a compelling and intriguing way, and in truth it is not all that tiresome, but it is incredibly long. After the second or third time the women (or one of the women) offer him sexual favours, only to refuse him at the last minute, the reader can’t help wondering why Mr Urfe doesn’t just walk away from the whole damned thing. He sees it through, and so will the reader, with perhaps a sense that the longueurs were justified, but I felt on this re-reading that John Fowles could easily have omitted at least two of Conchis’s long autobiographical recollections, and shortened the rest.

The essential attraction of The Magus lies, I believe, in what you could call extra-literary values.

You do not, for instance, have to read far into the novel to realize that it has a strong autobiographical content. It is known that as a young man John Fowles went to a Greek island to teach English at a large private school. The real island was Spetsai (or, as it has since become, Spetses), and it is in the same part of the Aegean Sea as the fictional Phraxos. He taught there until the summer of 1953, at the end of which he was sacked, in a similar way to Urfe although not for the same reason. The villa on the southern coast of the island is a real one, it is, or was, owned by a reclusive millionaire, and Fowles visited him there. After he left Spetsai, Fowles always swore he could not return to Greece (and did not until the end of his life, when he was taken there by a film-maker), and in general he said little in public about his time on the island.

However, his Journals from that sojourn have been published, and Eileen Warburton’s biography describes his days on Spetsai in detail. Bob Goosmann’s excellent website has more about this period. Fowles himself said, in the Foreword to the 1977 edition, ‘No correlative whatever of my fiction … took place on Spetsai during my stay.’ Even so, and knowing that reality is not the same as fiction, you can’t help experiencing a sense of curiosity about the events that are described in the novel. Fowles’s own denial, or at least his apparent need to make the denial, itself fuels the curiosity. Although many novels are written autobiographically, it is unusual to find one conducted with such intensity, so intriguingly, so enigmatically, and with so many undertones of plausible or even traceable reality.

And there is a sense of something larger, less well defined, behind the book. More than the story you read, more than the language you enjoy and even relish, more than the knowledge you gain of the characters, the reader acquires a sense of complex or profound material. The Magus seems to me to be at least partly about free will and randomness – this is never stated in such explicit terms, but as Urfe begins his quest to find out what had ‘really’ happened on Phraxos, he turns up more and more evidence that the conspiracy was wider than he imagined. Even chance encounters, a girlfriend picked up in a cinema, the landlady of a rented room selected from a postcard in a newsagent’s window, waiters, taxi drivers, newspaper vendors – they all seem to be directly or indirectly connected to the mysterious events at the villa. Maybe by this time Urfe was deep in paranoia, but then so too is the reader, also seeking some kind of rational solution.

I believe it is these extra-literary qualities which have given the novel its enduring qualities, and why it has always appealed (as Fowles himself noted, apparently ruefully) to younger or more open-minded readers. It shares with fantastic fiction that vague sense of ‘something other’, of stating or implying certain truths in outline, of suggesting that life is improvable or at least capable of change, of leaving much to the imagination while exactly and precisely stimulating it with imagined events and an invented story.