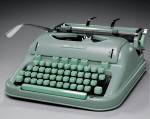

I was 21 and my future was determined – I wanted to be a writer. For my 21st birthday my father bought me a manual typewriter: a Hermes 3000 Portable. This replaced the machine on which I had learned to type: an elderly Olivetti belonging to my parents. The new Hermes was everything I wanted: a smooth, steady action, a nice clear 10-pitch typeface, and a solid base. This meant that I could balance it on my knees while I sat on the side of my bed – already my favoured position while writing. An extra bonus was that I knew somehow it was the same machine used by Brian Aldiss, who was then something of a role model for me.

I worked on the Hermes for about four years. I never thought of changing it or looking for a better machine, because I considered it to be perfect. On it I wrote all my early short stories, and a thousand letters. But then my friend Graham Hall won a scholarship to Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, and suddenly everything changed.

I worked on the Hermes for about four years. I never thought of changing it or looking for a better machine, because I considered it to be perfect. On it I wrote all my early short stories, and a thousand letters. But then my friend Graham Hall won a scholarship to Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, and suddenly everything changed.

Graham is now largely unknown, but he was a familiar and anarchic figure during the years of the British New Wave, in the 1960s. Like all of us he dreamed of being a writer, and in fact sold two or three remarkable short stories. The best of these was called “Sun Push”, published in the January 1967 edition of New Worlds SF. Three years later he and Graham Charnock co-edited an issue of New Worlds: December 1969. Graham Hall was a funny, highly intelligent and sensitive man, and was always entertaining and provocative company, but he had a weakness. He saw himself romantically as a doomed figure, and did whatever he could to confirm this by drinking heavily. I never once saw him drunk, but I also never saw him without a drink. He was to die of cirrhosis when he was only 32.

At the time of his scholarship to the American university, Graham had just bought his own Hermes typewriter, but unlike mine it was a huge manual, an office model. This was the period when the first electronic typewriters were coming on the market. They seemed likely eventually to replace both manual and electric typewriters. They were much quieter and less strenuous to use than manuals, and some even had a small memory bank to enable corrections. They were also much cheaper than electric typewriters, which were designed for office users and priced accordingly. Some of them used dot-matrix technology, but most of them printed with a daisywheel head. For writers, who spend hour after hour typing, the electronic machines felt lightweight and flimsy. Many writers in the USA at this time were using IBM Selectrics, with the golfball head and the distinctive typeface. (This typeface has become, incidentally, the expected and required font for all film scripts – even in these days of computers Hollywood producers will not read a single word of a screenplay unless it is in what these days we call Courier 12-pitch.) But for most of the people I knew in Britain at that time IBM Selectrics were beyond the pocket, and certainly were beyond mine and Graham Hall’s.

Graham’s reasoning for buying an office manual was sound, even if I didn’t share it. He said he wanted to future-proof himself: by buying the best-made office manual on the market he would own something that would last forever, and survive all the likely technological trends and gimmicks to affect typewriters.

To take up his scholarship in the USA, Graham needed a typewriter. His Hermes was far too unwieldy and heavy for travel. He asked me if I would be willing to trade mine for his, for the duration of his two years at Smith. I was not at all keen on this idea because I used my Portable every day and was completely at home with it. However, in the end I did reluctantly agree. I made Graham promise that he would treasure it and bring it back in one piece, and he solemnly promised he would. In any event, I would have his much larger machine as a replacement.

Shortly afterwards Graham flew away to the USA, leaving me with his Hermes Manual.

I didn’t like it much. It had a heavy action and the carriage required a hefty push at the end of every line. I had also grown attached to the Portable’s 10-pitch typeface (10-pitch = 12 characters to the inch), and was used to the smaller, neater face and could readily estimate line- and page-length. The Manual used 12-pitch (10 characters to the inch), and I kept missing the end of lines as I wrote. In short, I was disappointed with it and after a few weeks I bought a secondhand typewriter for £25 and began to use that instead. I passed Graham’s Hermes across to Charles Platt, who at that time needed a spare machine.

Time passed and several changes occurred. Charles later went to live and work in the USA, leaving most of his property (including Graham’s Hermes) in his old flat in London … which he now sublet. I continued to use my £25 manual typewriter for a while (my first two novels were bashed out on it), but it really wasn’t any good and in the end I invested in a secondhand electric machine, followed by several others as the years went by. And Graham Hall returned from the USA two years later with news that surprised and saddened me. Knowing how attached I was to my Hermes Portable he had felt unable throughout his entire sojourn at Smith to admit to me that it had been smashed by baggage-handlers on the outward flight. It was beyond repair.

Even though by this time I was used to electric machines, I had been looking forward to being reunited with my Portable. Graham felt the loss created a debt of honour. His stay abroad had given him the urge to travel, and he was planning to set out on a long worldwide tour almost immediately. He said I should keep the Hermes Manual, and added that one day he would return from his travels and buy it back from me. In the meantime he asked me to look after it, keep it in good repair, treasure it as I had asked him to treasure my own machine, and although it was a sentimental and rather silly agreement, I accepted.

Graham departed again to travel the world, and the Hermes Manual remained in Charles Platt’s sublet apartment. Graham sent occasional missives from Yugoslavia, India, Thailand, etc., but I was never to see him again. At the end of the 1970s he was in the USA, and by this time he was seriously ill. His drinking was beyond control and the inevitable hit him. He died in February 1980, a month short of his 33rd birthday.

A few years later, Charles came to visit me during one of his occasional visits back to the UK. He was getting rid of his London flat, and he asked me if I would at last take permanent possession of Graham’s typewriter. I was not all that keen, but we had another fairly sentimental conversation: we both knew Graham’s attachment to his old typewriter. Although I had no need of it, I felt I should take it.

By this time I was accustomed to working on an electric machine: I had a beautiful Adler electric, which had served me well for a long time. But I began to use Graham’s machine occasionally because I liked the change. I wrote several short pieces on it during 1982-1983.

Then came the computer revolution: I acquired my first PC in 1984, began word processing on it more or less straight away, and thoughts of typewriters, manual or electric or anything else, disappeared. I did keep Graham’s Hermes, though, storing it on a shelf in my study. I kept it clean and in repair, it had a new ribbon and I had a spare in my stationery box. The Hermes remained in the corner of my study for thirty years.

Then came the computer revolution: I acquired my first PC in 1984, began word processing on it more or less straight away, and thoughts of typewriters, manual or electric or anything else, disappeared. I did keep Graham’s Hermes, though, storing it on a shelf in my study. I kept it clean and in repair, it had a new ribbon and I had a spare in my stationery box. The Hermes remained in the corner of my study for thirty years.

But two weeks ago I moved my study to another room in this house: a smaller room upstairs, looking out across the garden. The smaller room meant a major reappraisal of what I really needed in a work room, and drastic culling actions began. Mick Smith, our local totter, soon spotted the skip on the drive and began ferreting through it. At the end he asked if there was “anything else”. Graham’s typewriter now stood more or less alone in my former study. Reader, I let it go.

Sorry, Graham. I did keep the spare ribbon, though.