From the plays of William Shakespeare, through the novels of the Bronte sisters, the social novels of Charles Dickens, the scientific romances of H. G. Wells, virtually every work of literature that becomes recognized as a classic was conceived and written in the first place for a popular audience. (The only exception to this generalization that I can think of is the work of James Joyce, which has achieved classic status without a groundswell of popular support.)

Recognizing writers in the present day who are likely to achieve long-term recognition as a classic author is a risky business. Popular success often comes about because of the public’s unpredictable reaction, or a wish to find an undemanding read, or because of a response to perceived matters of the moment. Happenstance comes into it, and so does the luck of timing. Best-seller success is therefore usually ephemeral. Can anyone seriously suggest that the ‘Grey’ novels of E. L. James, the ‘Twilight’ novels of Stephenie Meyer, the nonsensical best-sellers by the likes of Dan Brown or Jeffrey Archer, are destined for anything but the dustbin of literary history?

Who now reads, or even remembers, the author Hervey Allen? Or for that matter James Hilton, Dorothea Brande, Alexis Carrel, Franz Werfel, Munro Leaf? The works of Hervey Allen, and all the others, were discussed seriously and in detail in a book called Best-Sellers – Are They Born or Made? (1939, by George Stevens and Stanley Unwin). With the possible exception of James Hilton, who I suspect is remembered more for the iconic ideas of Shangri-La and Mr Chips than for present-day reading of the novels in which they appeared, all these writers have vanished more or less without trace. Yet in their day their books were immense popular successes. Ephemerality has struck – posterity has eluded them.

In 1981, John Sutherland published a book with a similar subject: Bestsellers – Popular Fiction of the 1970s. Sutherland then was interested in such popular novelists as Harold Robbins, Mickey Spillane, Michael Crichton, Jacqueline Susann, Frederick Forsyth, Jackie Collins, Mario Puzo, Len Deighton and a score of others. Most of these names are admittedly more familiar than those of Hervey Allen and his contemporaries, but I suspect their familiarity rests on the fact that popular films were made of their novels and are still being shown on TV. I also wonder how many people are still actually reading The Valley of the Dolls or The Dream Merchants or The Odessa File?

So the correlation between popular success and impending classics status is by no means certain. Because of this, one should be nervous of pointing to this or that contemporary success and predicting that posterity will accept it into its halls.

Certainly, the modern literary novel, at least in Britain, is not the place to look. Although they enjoy critical admiration and (one gathers) impressive sales figures, the books by writers like Ian McEwan, Julian Barnes and Martin Amis are unlikely to survive much beyond their authors’ physical demise. McEwan is a skilful stylist but he has an unoriginal mind and an unadventurous approach to fiction. Barnes is a writer of middle-class dilettantism, diverted into subjects rather than passionate about them, and one day will be regarded, I believe, as having many constricting contextual class and social assumptions. Amis is a more complex problem because he is ambitious and committed, and probably more intelligent than the other two, but as a novelist he peaked more than thirty years ago with his novel Money (1984), and his subsequent work has depended increasingly on verbal invention, much of it rather clumsy.

We are more likely to find literary posterity, or the possibility of it, in the genres. For instance, thirty years ago who would have guessed that Philip K. Dick would be seen, at least in the world of Hollywood studio films, as a paradigm of science fiction? Most of his novels were quickly written for commercial publishers, aimed at and read by a genre audience. But as a result of several hugely successful films, Dick’s many routine SF books have returned to print, he is taught in universities and schools, and he is generally regarded as the finest modern SF writer. Yet in 1981, roughly at the time Blade Runner was being filmed, John Sutherland gave Dick no more than a passing mention. Of course, this was largely because at the time he was not actually a best-selling author, he was still alive, his writing was past its best, and he was recognized mainly for his Hugo-winning novel The Man in the High Castle (1962).

Stephen King is the one contemporary author who seems to me destined for status as an enduring classic. His books are of course aimed resolutely at a popular audience, but his social awareness, his easy use of a myriad of contemporary cultural references, and his sheer bravado as a storyteller seem to ensure a timeless quality. In these respects his work strikes me as similar to that of Charles Dickens, but like Dickens he has written too much and not always well. Some of Stephen King’s books are over-long, and (like Dickens) he has stylistic and narrative mannerisms that, once noticed, can be annoying. However, his best work is intelligent, unexpected, personal, original in concept and told with ruthless skill.

I think the jury is still out on the work of J. G. Ballard, at least as far as enduring popularity is concerned. Since his death in 2009 Ballard’s reputation has grown steadily, so there is room for hope. Although most of his best work was originally published in the kind of popular science fiction magazines despised by the literary establishment, in the years following the publication of Empire of the Sun (1984) his work was taken up and accepted not only by critics and the literary world in general but by the book-reading public too. Because some of his work from the end of the 1960s is avant-garde and ‘controversial’ (I’m thinking of his Atrocity Exhibition period, with its references to American presidents of the day, the Vietnam War, and so on), long-term status as a classic writer is not certain. But the early short stories, as well as the novels The Drowned World, The Burning World, The Crystal World and Crash, are distinctively original, metaphysical in impact and told in almost transparently lucid prose, waiting to be discovered by those who have so far not done so.

Then there are two writers of fantasy: J. K. Rowling and Terry Pratchett.

Rowling’s Harry Potter books have been so massively popular, and so widely discussed, that there is little point in adding a further encomium. Except to say that my own children were at exactly the right age to discover and be enchanted by the books as they appeared, so that I was a close witness to the impact the books (devotedly written for a wide and popular audience) had on them and their friends. It’s worth pointing out that that generation of first Harry Potter readers is now approaching the age of their own early parentage – the wheels of posterity are turning smoothly.

Finally, the works of Sir Terry Pratchett. I have been provoked to write this essay today by an article in the Guardian’s blog, by the newspaper’s arts correspondent Jonathan Jones. As a display of closed-minded prejudice, and an astonishing willingness to brag about it, there have been thankfully few precedents. Here is how Jones starts:

It does not matter to me if Terry Pratchett’s final novel is a worthy epitaph or not, or if he wanted it to be pulped by a steamroller. I have never read a single one of his books and I never plan to. Life’s too short. No offence, but Pratchett is so low on my list of books to read before I die that I would have to live a million years before getting round to him. I did flick through a book by him in a shop, to see what the fuss is about, but the prose seemed very ordinary.

Unsurprisingly, the online comments on this pathetic piece of ignorant journalism have swarmed in (at the time of writing, just under one thousand), and for once almost all of them agree with each other. I will be surprised and disappointed if Mr Jones retains his job with the Guardian, at least in the capacity of an arts correspondent. I have rarely seen a letter of resignation so overtly and shamelessly revealing as this. I was forcibly reminded of a letter my old friend John Middleton Murry wrote to the Observer many years ago on another, not dissimilar, matter: ‘I note your organ does not have a reporter in Antarctica, and suggest that this would be a suitable posting for Mr Martin Amis.’

I should add that Terry Pratchett and I were respectful colleagues rather than personal friends. We knew each other better in the days when we were teenage hopefuls, trying to get our first stories sold. The years went by, we found our publishers and we went our separate ways. I doubt if Terry ever read my books – I read only a few of his. Terry does not need me to defend him – Jones’s article is contemptible.

But I would say that of all the writers I have ever known, or the books I have ever read, Terry Pratchett’s seem to be a dead cert for long-term classic status. They are written for a popular audience, so fulfilling the first condition. They have been commercially successful, not just in Britain and the USA, but in languages and countries all around the world. The books are not liked by many: they are loved and admired by millions. Uniquely, in the profession of writing, where commercial success often turns a writer’s head and (to mix a metaphor) turns him or her into an asshole, Terry Pratchett remained approachable, unpretentious, sane and generous. His immensely popular appearances at Discworld conventions were marked by his geniality, openness and amusing manner, and a shared respect between author and audiences. His premature death was a cause of sincere mourning to all those readers, most of who never had the chance to meet him.

His work is written well – no matter what Jones says about ‘very ordinary’ prose, Terry Pratchett’s novels are stylistically adept: good muscular prose, not mucked around with for effect (except sometimes!), enlivened by wit, sharp observation, a unique take on the world at large and whatever the subject of social satire might be for the time being, a brimming sense of fun and the ridiculous, and overall an approach to the reader that feels inclusive, a letting in on the joke, an amused welcome to the world he is writing about. All his books contain bizarre cultural cross-references – part of the fun is spotting them. Some of his jokes are genuinely original – I always liked the one about the Australian bush hats with the corks, and the other one about the vampire photographer who used a flashgun on his camera. Millions of people – not the appalling Mr Jones, a spectacular scorer of own goals – will recognize these references with a sense of remembered joy.

I hope Jonathan Jones packs plenty of warm underwear for his next job.

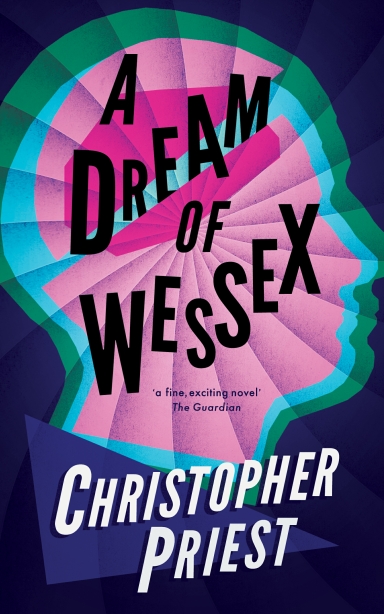

This is the cover for Valancourt’s new paperback edition of A Dream of Wessex, which they will be publishing in the USA in March.

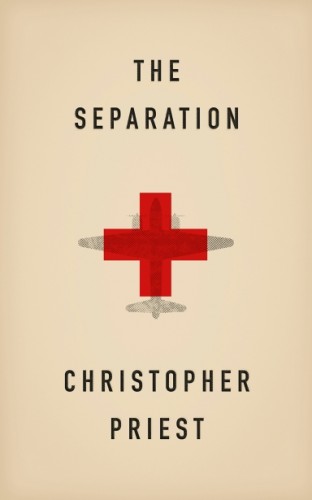

This is the cover for Valancourt’s new paperback edition of A Dream of Wessex, which they will be publishing in the USA in March. Meanwhile, here is the cover illustration Valancourt have put on their US paperback edition of my 2002 novel The Separation. This was published back in June 2015, but for some reason the copies Valancourt sent to me did not reach me. I only became aware recently that the book was already out. Until now, or at least until June last year, The Separation had never achieved a mass-market paperback in the USA, so this new release is especially pleasing to me.

Meanwhile, here is the cover illustration Valancourt have put on their US paperback edition of my 2002 novel The Separation. This was published back in June 2015, but for some reason the copies Valancourt sent to me did not reach me. I only became aware recently that the book was already out. Until now, or at least until June last year, The Separation had never achieved a mass-market paperback in the USA, so this new release is especially pleasing to me.