My obit of Terry in the Guardian is here. I knew Terry for more than half a century: we met in 1964 at a convention in Peterborough. He was still at school – I was the world’s worst trainee accountant. We both moved on a bit afterwards. I believe his conduct as a successful author was and is exemplary. The quality of his writing never failed. I would say more, but it is already in my Guardian piece.

Author: chris

“Open Your Balls”

I went to see the new film Mortdecai (2015) with a feeling of duty to an old friend. (Kyril Bonfiglioli, who wrote the novels.) The reviews of the film have been almost universally awful, and after Nina and I saw the trailer last week I couldn’t help thinking it was going to be something to get through and keep quiet about afterwards.

Bon was such a great and long-lasting friend. He bought, published and even paid for my first story (eight guineas!), but that was not the sole basis for a friendship that lasted twenty years. In the mid 1970s he began writing the Charlie Mortdecai novels, completing three of them before the dread consequences of the demon booze caught up with him in 1985. He also wrote a non-Mortdecai novel, All the Tea in China (1978). After his death, an unfinished fourth Mortdecai novel was found in his papers – this was completed a few years later by Craig Brown.

The Mortdecai books have recently been reprinted by Penguin Books. I read them as they came out in the 1970s – they struck me then as fabulous: fast-moving, extremely intelligent, funny, self-awarely xenophobic, ingeniously nasty, and full of bits you want to read out aloud to others. At the beginning of the first book (Don’t Point That Thing at Me) he wrote: “This is not an autobiographical novel: it is about some other portly, dissolute, immoral and middle-aged art dealer.” I would recommend the books without qualification if it were not for the fact they are now more than 30 years old, and the way we perceive the world has changed a bit since then. Well, all right, then: give them a go!

There is also a book called The Mortdecai ABC, by Margaret Bonfiglioli, published by Viking in 2001. This is a wonderful compendium, arranged in a kind of alphabetical order, of everything and a bit more about Bon. There is, for instance, a series of biographical sketches – a few sample headings include Car Crashes, Hidden Jokes, Food, Lies, Parrot, Waistband and Waistline, Tea. All his editorials from Science Fantasy are here, and every short story he ever wrote. Letters to his publishers. And letters to friends: a whole chapter reprints some of the correspondence between Bon and myself in the 1970s. In her Introduction, Margaret (Bon’s ex-wife) writes: “How did I happen to put together this book? Laughter began it.”

There is also a book called The Mortdecai ABC, by Margaret Bonfiglioli, published by Viking in 2001. This is a wonderful compendium, arranged in a kind of alphabetical order, of everything and a bit more about Bon. There is, for instance, a series of biographical sketches – a few sample headings include Car Crashes, Hidden Jokes, Food, Lies, Parrot, Waistband and Waistline, Tea. All his editorials from Science Fantasy are here, and every short story he ever wrote. Letters to his publishers. And letters to friends: a whole chapter reprints some of the correspondence between Bon and myself in the 1970s. In her Introduction, Margaret (Bon’s ex-wife) writes: “How did I happen to put together this book? Laughter began it.”

How sad it was to read the previews and reviews of David Koepp’s film Mortdecai. Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian wrote: “The poster is awful. The premise is awful. To be frank, quite a lot about it is awful: a middle-aged comedy caper of the kind not seen since Peter Sellers’s final outings as Clouseau and Fu Manchu.” Geoffrey Macnab in The Independent said: “an incredibly convoluted script involving a stolen Goya painting, random changes of location (we are whisked, for no particular reason, from London to Moscow to LA), too many gags involving vomit and rotting cheese, and some incredibly dull and dim-witted dialogue that would barely have passed muster in a bad British 1970s sitcom.” Things were no better in the USA, where box office takings were said to be some $50 millions below budget. Josh Slater-Williams in SoundOnSight wrote: “a cataclysmically unfunny, unbelievably tedious disaster of baffling misjudgments and multiple career lows that feels as long as Shoah, and only a little less harrowing.” The end of Johnny Depp’s career was doomily predicted by all and sundry.

Well, we went to see it anyway. I loved it. Nina loved it. We both laughed out loud several times, laughed quietly most of the time, and at very worst were agreeably amused for the rest. The audience enjoyed it too. It has a tremendous pace, scurrilousness, wit, a ridiculous heist, stupid violence, jokes about moustaches and penises and vomit and smelly cheese and foreigners. What more do you want?

Do try to catch the film while it is still around in theatres. And don’t miss the books!

Standing on shoulders

I am late to the party: Station Eleven was published in the UK about four months ago and has won many favourable reviews, it was a best-seller in the USA and was shortlisted for the National Book Award. I suspect more accolades are to come for this remarkable novel. We enjoy books on a personal level, and if we set out to write a favourable review afterwards what we are really doing is trying to express that feeling in objective terms. In other words, we translate enjoyment into admiration.

I am late to the party: Station Eleven was published in the UK about four months ago and has won many favourable reviews, it was a best-seller in the USA and was shortlisted for the National Book Award. I suspect more accolades are to come for this remarkable novel. We enjoy books on a personal level, and if we set out to write a favourable review afterwards what we are really doing is trying to express that feeling in objective terms. In other words, we translate enjoyment into admiration.

But this time, instead of trying for critical distance, let me give a more subjective account of this book. It involves an indirect approach.

In the early 1960s, barely out of adolescence and working unhappily in a London office, I discovered the existence of the National Film Theatre. It showed in repertory the sort of films I had never seen while a child in the bosom of the family: the NFT had foreign films, experimental films, old films, independent films, arthouse films. I joined with alacrity, and soon received their current programme: they were about to start a retrospective season of films by Ingmar Bergman. I sent off for tickets.

During the following two weeks I saw four Bergman films at the NFT: Sawdust and Tinsel, Summer with Monika, Wild Strawberries and The Seventh Seal. All were in black and white; the dialogue, of course, was in Swedish (and delivered in theatrical tones, punctuated with long silences); the subtitles were erratic and shaky; the prints were scratched. The themes were sexuality, impotence, love, humiliation, betrayal, pride, death. It was a transforming experience. Nothing before had ever intrigued or satisfied me so much. A mood of gloom, wonder, excitement and ambition gripped me. Later, I was to see many more Bergman films, but the shocking impact of those first four was never quite to be repeated. For me, ever after, Bergman’s work has been an exemplar, a precedent, a goal.

The first of Bergman’s films that I saw, and therefore the one which had the profoundest effect on me was Sawdust and Tinsel. This is set in a ramshackle travelling circus, the wagons pulled by exhausted horses. The players’ circus costumes are threadbare, their audiences minimal. The mood is defiant, jealous, defensive, mystical.

Much of the action in Emily St. John Mandel’s novel Station Eleven describes a ramshackle group of survivors, travelling in engineless, horsedrawn pick-up trucks, working their way through the remains of the state of Michigan after a global disaster. All the characters are actors or musicians, or people who have learned since the disaster to be actors or musicians. They call themselves the Symphony, and at each of their stops they put on their threadbare costumes and perform. Sometimes they mount King Lear or Hamlet; at other times they play classical music. They also have to hunt, scavenge and kill, but at the end of the day they set out chairs for whatever audience they can attract, the conductor taps her baton on the stand and they start playing a Beethoven symphony.

The concerns and eventual destiny of the characters are different in detail from those of Bergman’s, but the subtlety, complexity, doggedness and despair of Mandel’s characters resonate strongly with his.

Around the same time as my discovery of Ingmar Bergman, I came across a novel well liked in the SF world, although at the time I had no knowledge of that. To me it was just a book I happened to buy. It was Earth Abides, by George R. Stewart. Stewart was an expert in place-names, an historian and a professor of English at Berkeley. He appears to have had no knowledge of or connection with the science fiction genre. Earth Abides was not his only novel, but it was his only purely speculative work.

It describes the collapse of civilization after a global pandemic – at first the central character, Isherwood Williams, believes himself to be the only survivor, by a fluke. Later he discovers one or two other survivors. Human society tentatively begins to re-form.

An aura of loss, death, guilt, failed responsibility hangs over the background to the novel, not unlike in Bergman’s early films. There is a broader outlook, though: Earth Abides is also about the impact humans have had on the physical environment, and there are many scenes depicting the changes to the world that follow the demise of humanity, all of them thrilling and moving to read. Stewart was an ecologist, a green, decades before that awareness had any currency outside the work of a few specialist scientists.

This was powerful stuff for a teenager to read, and it left a lasting impression on me. I still believe that because of this book my consciousness about pollution, climate change, waste of fossil fuels, the dangers as well as the benefits of a technological society, was raised many years before these issues became understood in the general world. I also know that this is not a unique reaction: the book is regarded as a classic by many of the people who came across it half a century ago.

Bergman and Stewart – they are giants in my life. I can offer no higher compliment to Ms Mandel than to say that while reading her novel these potent sensibilities were re-awakened in me. Perhaps a new generation will draw from Station Eleven something of the same understanding of the frailty of life, or of the interconnectedness of the world, or of the wonderful and inspirational gloom that I drew many years ago from these giants. Her novel is complex, subtle, wise, beautifully written, layered, original and often moving. I cannot commend it more highly.

Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel, Picador, 2014, ISBN: 978-1-4472-6896-3, £12.99

L’Adjacent

Here is the beautiful new cover for the French edition of The Adjacent. The artist is Aurélien Police, and the book will be published in April, by Lunes d’Encre (Denoël). Editor: Gilles Dumay.

I will be in France during May, firstly at Étonnants Voyageurs in St-Malo (23-25 May), then at Imaginales in Épinal (28-31 May).

The Stars my Mutteration

This is a public service entry:

Oh, my God. / Cooper, there’s no point using our fuel to – / Just analyse the Endurance’s spin – / What’re you doing?! / Docking. / Endurance rotation is 67, 68 RPM – / Get ready to match it on the retro-thrusters – / It’s not possible – / No. It’s necessary.

When I wrote the blog entry immediately below this one I had been planning to write a review of Christopher Nolan’s new film, Interstellar, which I saw at the end of last week. That idea was hijacked by the sudden arrival of my copies of the Gollancz edition of A Dream of Wessex. Because I was thinking about Nolan I remembered I had always wanted to write about the similarities between that novel and his earlier film, Inception. So I did that instead. (See below.)

Interstellar is a problem, a long, poorly written and second-rate film with a wide popular appeal, so I briefly decided enough was enough. Other people, notably Abigail Nussbaum, have elegantly and convincingly demolished it. No point me adding to Nolan’s woes.

But yesterday there were several stories in the press, on the radio and all over the internet about the sound level of the new film. Many audiences have complained that the music and sound effects are too loud in Interstellar, while the dialogue is too low to be heard and followed. There were stories of people demanding their money back, and a theatre in Rochester NY putting up a sign saying that their sound equipment was not at fault: the film’s soundtrack had been recorded that way. Christopher Nolan himself came forward to confirm this, calling it ‘a carefully considered creative decision’, using the dialogue as a sound effect, to ‘emphasize how loud the surrounding noise is’.

The composer, Hans Zimmer (a highly regarded film composer, and rightly so), is himself totally unapologetic, and says so here. But as writer and director of the film, and someone who presumably oversaw the editing and sound mixing, Christopher Nolan has the greater responsibility.

Anyone knows the reality. The ‘surrounding noise’ of space is silent. Space is a vacuum – it is incapable of carrying sound. How Hans Zimmer’s loud music can be heard in space is a mystery only Nolan can explain.

(An earlier Nolan film, his adaptation of my novel The Prestige, had similar problems with music and dialogue recording. Although overall I admired the film, I have always been concerned with these two crucial weaknesses. Until Nolan came forward today to explain his creative decision, I had assumed the muttered dialogue was a mistake, a consequence of inexperience.)

Returning to Interstellar: By chance I am one of the few people who had no problem with the dialogue of this extremely long film. The version we saw was subtitled ‘for the hard of hearing’, so every word of the script was plain. I can therefore report that much of the dialogue creatively hidden from the audience is similar to the short extract above, and the rest is … not exactly Shakespearean pentameters.

Nolan clearly uses dialogue as a sort of fill-in noise. He calls it a sound effect. For him, words are something he has to get the actors to come out with while they’re performing set-pieces or going through spectacular scenes.

This was particularly true of Inception, which had one of the worst-written scripts I have come across. I winced at its clumsiness several times while watching it – a later look at the shooting script confirmed the clodhopper style was not my imagination. (Christopher Nolan was credited as writer.) Interstellar came from a different source: it was originally written solo by Jonah Nolan for a planned film by Steven Spielberg – that original script was very different from the finished film. Jonah’s original can be read on the internet, where there are several discussion pages about the many differences between the two. As Christopher Nolan is credited as co-author of the final screenplay, we assume that he was responsible for the changes when he took over the project from Spielberg. He has said so himself.

Dialogue is crucial to film: the words given to actors to deliver humanize the story, make it comprehensible to the audience, create characters with whom we can sympathize or at least understand. Nolan’s argument that dialogue is just another sound effect is weak and unconvincing, and is of course an evasion of something much more serious. If the dialogue he has written consists of people mumbling to themselves, or shouting about retro-thrusters over the noise in space, then maybe he is writing the wrong kind of dialogue in the wrong kind of film.

A Dream of Inception

Here is the Gollancz paperback of A Dream of Wessex, just released. The novel has been unavailable for several years, so I’m pleased to see it in this attractive stripe. For those who are interested in such things, it was first published as a Faber hardcover in the UK in 1977, which makes it getting on for forty years old. I imagine some aspects of it will now seem dated, but maybe that’s how it should be.

Here is the Gollancz paperback of A Dream of Wessex, just released. The novel has been unavailable for several years, so I’m pleased to see it in this attractive stripe. For those who are interested in such things, it was first published as a Faber hardcover in the UK in 1977, which makes it getting on for forty years old. I imagine some aspects of it will now seem dated, but maybe that’s how it should be.

Wessex is not so dated, though, that some people were prevented from pointing out the similarities between this book and Christopher Nolan’s film Inception, released in 2010, a mere thirty-three years later. Both deal with the exploration of the dream state, and how that impinges on reality, or our perception of reality. I say straight away that I did not notice anything more than minor coincidences myself, and never mentioned the few bits I registered. Anyway I would be reluctant to make what might seem an allegation that Christopher Nolan had nicked some of my material. He and I have a known professional relationship, and I assume he is familiar with most of my books, even if he hasn’t read them closely.

The first time someone pointed out the several resemblances between the two I was surprised that I had missed so many of them, but after more people had gently explained them to me I began to see.

Like many people who went to the film, I had been dazzled by its surface, the astonishing CGI effects and photographic trickery. I found the plot more or less incomprehensible, though – it was a kind of mix of James Bond antics (buildings collapsing, explosions, chases, guns, snowmobiles), and men in business suits mouthing lines about reality and dreams, and finishing each other’s explanatory sentences. I gave up trying to follow the plot after this pungent exchange:

So how did we end up at this restaurant? / We came here from … / How did we get here? Where are we? / Oh my God. We’re dreaming. / Stay calm. We’re actually asleep in the workshop. (Pp. 66 – 67 of the shooting script, published by Insight Editions.)

The urge to describe and explain the plot through dialogue is incidentally a similar feature of Nolan’s current release, Interstellar. In this three-hour spaceship adventure there are extended dialogues between astronauts in spacesuits, risibly explaining orbits, trajectories, relativity and wormholes to each other, finishing each other’s explanatory sentences, and drawing primary-school level graphics to convince themselves the plot is going OK. This was so nakedly aimed at the assumed ignorance of the audience that it was embarrassing. As soon as a film engages in trying to meet the imagined comprehension of an audience, it loses itself. Consider instead the success of Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin (2013), which showed everything and explained nothing.

But back to Inception. Some of it was genuinely beautiful and mysterious to watch: the city of Paris inverting, trick mirrors along the banks of the Seine, a super-slo-mo shot of a van plunging into an icy river from a bridge, a ruined city slowly collapsing into the sea. These are all Nolan’s creation, or that of the CGI studios who developed the images for him.

Some of it, I saw belatedly, did have an uncanny likeness to my novel. There is, for instance a scene below ground, in fact in the basement of Yusuf’s pharmacy, in which a large number of people are shown to be sharing a continuous dream, one from which it is impossible or dangerous to withdraw. This might be part of a dream within a dream! The situation exactly matches the MacGuffin in A Dream of Wessex, which is about a scientific experiment in which a large number of people go below ground, and create a pooled dreamworld, one which is so plausible that it becomes hard for them to distinguish it from reality. Withdrawal from it is difficult and dangerous. And both film and book deal with the risks attached to creating a second or third level of dream, within the dream.

I’m nearly forty years away from the writing of A Dream of Wessex, and looking at it now I find it has some surprises for me. I make no claim for it. It is what it is, and in my own writing chronology it was a tentative first step towards the material in The Affirmation, which followed it. Wessex is a sort of transition from what I wrote in the early days, to the fiction I wrote later. (Some people, not I, might argue this was a progress from futuristic or ‘science’ fiction to a more sophisticated ‘speculative’ fiction, which is, interestingly, the exact distinction Christopher Nolan makes in the Introduction to the screenplay of Interstellar, also published by Faber. His film about astronauts and spaceships and alien planets is, he says, speculative fiction not science fiction. It lacks futurism, he claims, and is true to the contemporary world.)

But I’ll say this of Wessex: it has the quality of a direct narrative, where the plot is revealed through the characters: their actions, their relationships, their discoveries. They don’t sit around discussing the plot, and helping each other explain complicated ideas – they get on with the story. Maybe that’s how we did it in the old days …

A Dream of Wessex: Gollancz, 2014, 240 pp, £8.99, ISBN: 978-0-575-12153-9

Inception – the Shooting Script: Insight, 2010, 240 pp, £10.99, ISBN: 978-1-608-87015-8

Interstellar – the Complete Screenplay: Faber, 2014, 380 pp, £20.00, ISBN: 978-0-571-31439-3

A New Affirmation

Here is the cover image of a brand-new US paperback of my 1981 novel, The Affirmation. This is scheduled to be published in January 2015 by the superb American indie publisher Valancourt, with a new introduction written by myself.

Here is the cover image of a brand-new US paperback of my 1981 novel, The Affirmation. This is scheduled to be published in January 2015 by the superb American indie publisher Valancourt, with a new introduction written by myself.

The Affirmation has been effectively unobtainable in the USA almost from the moment it was published in hardcover by Scribner. Their edition lacked a certain feeling of conviction and the book received mediocre reviews. I have memories of coming across three rather battered copies a few weeks after publication, on sale in a branch of Crown Books in Houston — they looked sad and unloved, and I was tempted to buy them myself to put them out of their misery. A year later, when I was back in Houston, I found the same three copies still on sale in Crown Books, but now they were priced at 5¢ each and still had no buyers. It is moments like that which remind writers of their lowly place in the universe. The Affirmation has never had a paperback edition in America until now.

It is not the best-known of my novels, but it has always had a remarkable effect on a significant number of readers. Although it was written in what now seems a distant part of my life, I still regard it as my ‘key’ novel. I go into this in more detail in the introduction.

An odd footnote: Nielsen’s Bookdata no longer lists the Scribner edition of The Affirmation, but a search in the database for the ISBN (which without fear of contradiction or error I can state is 0-684-16957-6) reveals a book called The Affirmation by one Oliver Trager. I generously assume this is not copyright theft, but what Martin Rowson the cartoonist calls (and sometimes draws) a fur cup. I assure Nielsen’s and Mr Trager that I really am the true author of the book, and I have numerous different editions to prove it. I hope that enough readers in the US will now discover the book for themselves.

Valancourt’s interesting website may be viewed here. And an essay I wrote about three years ago, concerning the maddening reviews The Affirmation received, can be found on this website.

His Beast Yet

Bête is a novel of well chosen sly references – lines from pop songs, other books, puns on cultural icons, TV shows, bits of well known slang – but one of the slyest, and perhaps best chosen, since we know Adam Roberts is an English academic, is on the last page. ‘This is the best of me,’ says Roberts on his Acknowledgements page. Is that an acknowledgement, or a boast? Interest aroused, I go in search.

Bête is a novel of well chosen sly references – lines from pop songs, other books, puns on cultural icons, TV shows, bits of well known slang – but one of the slyest, and perhaps best chosen, since we know Adam Roberts is an English academic, is on the last page. ‘This is the best of me,’ says Roberts on his Acknowledgements page. Is that an acknowledgement, or a boast? Interest aroused, I go in search.

It takes some tracking down, but the remark comes from Sesame and Lilies, by John Ruskin. (It was also quoted by Edward Elgar on the manuscript score of The Dream of Gerontius.) Here it is in full, in quotation marks because Ruskin placed it in them:

‘This is the best of me; for the rest, I ate, and drank, and slept, loved, and hated, like another; my life was as the vapour, and is not; but this I saw and knew: this, if anything of mine, is worth your memory.’

The context is Ruskin’s definition of the difference between the sort of book that conveys news or amusement and a ‘true’ book, which is written for permanence. Of permanence, Ruskin says, ‘The author has something to say which he perceives to be true and useful, or helpfully beautiful. So far as he knows, no one has yet said it; so far as he knows, no one else can say it.’ Unless I am completely misinterpreting Adam Roberts’ intentions, I take this to mean he was aiming high with Bête, a book no one else can or would write, worthy of our memory.

That’s a classy boast, and I like it. After one novel a year for the last decade and a half, and heaven knows how many parody novels, he’s entitled to that. But is it the best of him?

It’s an unusual novel, unusual even for Roberts, whose fiction has never been what might be called expectable, but also unusual within the genre of fantastika. Like much of his work it has a distinct satirical streak, but unlike the earlier novels of his I’ve read, which depended on exact but often dodgy plotting, it is almost sluttishly freeform. It therefore escapes the need to make sense in plot terms. In fact, there is hardly any discernible plot – just a sequence of events, many of which are static or internalized, and the rest of which are the sort of long rambling conversations, full of stupid generalizations and cheerful abuse, overheard in a pub.

What will happen in the course of the story seems fairly predictable, once you understand the parameters of the set-up. Animals have gained the use of words, through the fitting of an AI chip. With the gaining of words comes an animalistic point of view, and, concomitantly, the power of persuasion. It’s not long before they are running things: e.g., farms are worked by humans, with the beasts occupying the farmhouse, so to speak. A shade of Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945) is being summoned of course, and Adam Roberts, one of our most intelligent and well read writers, knows exactly what he is doing. The famous last line of Animal Farm is one of the many cultural references that are scattered throughout the book.

The sequence of events is not all that exciting: the oddly named narrator, Graham Penhaligon, a former abattoir worker, butcher and farmer, lives rough in and wanders around the Thames Valley. He is in squalid circumstances for most of the story: unwashed, starving, sleeping rough in Bracknell Forest, killing animals for food – he spends half the book crippled by a damaged Achilles tendon. He is living on the fringe of a weird and dysfunctional society, where isolated houses, villages and suburban towns are empty (there’s an ebola-like epidemic called Sclera killing humans in the millions), while the M4 motorway is a hell of rushing vehicles and roadside squatters. Canny animals (i.e. those fitted with AI chips) are fighting back, and in Graham’s case biting back. He’s a high-profile enemy to the new master race, having notoriously slaughtered a talking cow in the first five pages of the novel. He meets and falls in love with Anne, a cancer victim, and after her death, a haunted and lonely man, he seeks a sort of revenge on the world until another kind of solution is offered to him.

So it’s an unusual novel, but does that make it any good? Not all unusual books are. Most of us would accept Animal Farm and Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker (1980) as good novels — properly referenced here, as their precedence is clear — but Will Self’s recent modernist novel Umbrella (2013) was both unusual and more or less unreadable. One also remembers with a shudder some of the modernist attempts at New Wave stories from untried SF writers in the 1960s. In large, the genre of science fiction is in formal terms unadventurous, employing conventional narratives and plot structures, depending more on its exploration of ideas than deep characterization or beautiful or experimental prose, so a book like Bête tends to stand out purely for its way of being told.

As anti-heroes go, Graham Penhaligon is a consummate act. His narrative is remarkable for his self-loathing, cynicism, intolerance, stubbornness and gritty determination. When he loses the love of his life the contrast in his feelings is telling. But most of the time his attitude and manners are appalling, and you can’t help liking him for that:

Eventually a junior officer came to fetch us. ‘You all right going upstairs with that stick?’ he asked me, in a voice plumped with the peculiar smugness of the very posh. ‘It’s just that the elevator is on the fritz.’

‘I can walk,’ I replied. ‘Unless you fancy giving me a fucking piggy back, lard-face.’

The answer to my question above (‘does that make it any good?’) is yes, but I think Bête is good mainly in what it tells us about the progress of the writing of Adam Roberts, rather than as a novel in itself. Although it is clearly likely to be one of the stand-out novels of 2014, I believe in overall terms Bête’s unusualness of attack is not enough to counteract the feeling of familiarity created by the smallness of its scale, the limits of its ambition. In the end, the society is drawn too vaguely, the revolution amongst the animals is unconvincing and slightly risible, the puns too many, the references to pop music and TV too dating, the events too meandering. However, the real reason to read this book is to see a good writer getting better, and doing so in unexpected and uncommon ways. The prospect of a new novel from Roberts is always a matter of expectation, but I believe after Bête we should be genuinely keen to see what he will come up with next.

Bête by Adam Roberts. Gollancz, 2014, ISBN: 978 0 575 12768 5, £16.99

Let the notebook be the judge

Ian McEwan and I are almost contemporaries. He is five years younger than me, and his first book was published about five years after mine. The mid-1970s was a good time for a young, apparently radical writer to appear, because around then several literary commentators had been perceiving there was a vacuum, where no young or apparently radical writers were coming through. McEwan, an alumnus of the University of East Anglia’s Creative Writing Course, then emerged and was greeted as the new best hope. Like a lot of people I read his first couple of books (both of them story collections), and I was impressed. I saw him as a bit of a literary rebel, independent-minded, someone who wasn’t going to be easily categorized. He was clearly gifted, had a nice sense of the macabre or disgusting, and his use of English was excellent.

I was not alone, though, in noticing that some of his stories bore remarkable similarities to stories by other writers. The first of these was ‘Dead as They Come’ (1978), which appeared in his second collection, In Between the Sheets (1978). This was almost exactly the same story as J. G. Ballard’s ‘The Smile’, published two years earlier. Several people pointed out other alleged examples of McEwan similarities, but the most publicized from this period was his first novel, The Cement Garden (1978), found by many to be a retread of Julian Gloag’s Our Mother’s House, published fifteen years earlier. Gloag himself was so irate about his work being pilfered that he wrote a novel based on McEwan’s assumed plagiarism, called Lost and Found (1983).

McEwan himself of course denied being a plagiarist. At the time I believed him, but I also thought that he was guilty of something almost as bad for a writer serious about his work. He wasn’t imagining properly, not thinking deeply enough.

He kept producing stuff that was like other writers’ work. It happens from time to time to many writers, but most of those coincidences are one-offs. McEwan has been dogged by accusations of copying all his career – it’s beyond coincidence. So what was going on if it wasn’t plagiarism? I came to the conclusion he had a lightweight imagination: he would see something on TV, or he would read a newspaper article, or hear an anecdote of some kind, then think he could get a story out of it. If you respond in such a shallow way, it’s inevitable that somewhere else in the world another writer will have had the same ‘inspiration’. Later I discovered from a television interview that McEwan carried his notebook everywhere and filled it with thoughts – some of them were his own, but many of them were extracts he found in other books. Nearly all writers use notebooks, so that doesn’t make him unusual. But apparently McEwan neglected to note the source – he made the excuse that years later he might come across something in one of his notebooks and not realize it was by another writer.

In recent years his copying has become even less ashamed than before. He was castigated in the press for copying out (and minutely modifying) passages from Lucilla Andrews’ memoir No Time for Romance, and including them in his novel Atonement. McEwan wisely kept his head down and waited the storm out, which duly blew over, but the plagiarism remains like a malignant lump in a sensitive part of the body. (Atonement is one of his most widely read novels.) When I reviewed his novel Solar (2010), I pointed out that a central plot-turn was obviously based on an identical sequence in the film Groundhog Day. Later in the same novel, he reported as a real event a familiar urban myth (the one about unwittingly sharing chocolate biscuits, or potato crisps, with a stranger in a station buffet), but on second thoughts he made a belated ham-fisted attempt to convert it into a serious point about industrialization.

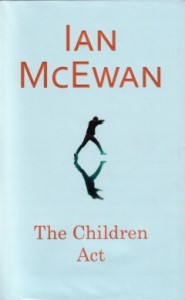

And now here we are with his most recent novel, The Children Act, and he is still revealing either his lightweight thinking, or his willingness to copy stuff down and transfer it to his novel. It’s done a bit more subtly this time, and his source is impeccable, but he remains in literary terms a copyist.

The plot of the novel, though, is original to McEwan. Here it is: Fiona Maye is a middle-aged woman whose husband suddenly announces that he wants to have an ‘ecstatic’ sexual affair with a younger woman. He walks out on her. Fiona immediately has the locks changed. A few days later she finds her chastened husband sitting in the hall outside their apartment, his possessions scattered around. She reluctantly lets him back in, and they co-habit in separate rooms. By the end of the book they have reconciled, and are sleeping together again.

That’s a thin plot for a 200+ page novel, so there must be something more? Of course: there’s a sub-plot, and this concerns Fiona’s job. She is a High Court judge in the Family Division, and she has to make a tricky decision about an adolescent boy whose parents are Jehovah’s Witnesses. He is dying of leukaemia. The parents will not agree to the blood transfusion that might save his life, which the doctors feel they have a Hippocratic obligation to provide. Fiona finds for the doctors, the transfusion goes ahead and the boy survives. She reads his romantic poetry. He begins stalking Fiona and on catching up with her asks if he could move in and live with her. They share a brief but passionate kiss. Afterwards, Fiona thinks better of this, and cuts off contact. A few months later she hears that after the boy turned 18, and was therefore capable of making his own decisions, the leukaemia returned. He himself refused another transfusion, and died.

This sub-plot is much more complex and interesting than the main plot (although it does include an overlong description of court proceedings, page after page of barrister characters, legal references, applications, statements, witnesses, meticulous post-Rumpole stuff without John Mortimer’s wit), but a sub-plot it remains.

Unfortunately, the dying Jehovah’s Witness is not a McEwan invention but an actual case, presided over by a leading Appeal Court judge in 2000. By McEwan’s own admission, freely made and repeated, he met the judge socially, rather admired the elegant linguistic style of top judges, made friends with the judge and listened avidly to his recollections of tricky decisions made in the past. (If you’re wondering how this formerly radical and independent literary firebrand came to meet top judges socially, the story is here: ‘Some years ago I found myself at dinner with a handful of judges’. As one does.)

Of course, McEwan attends to details, introduces differences – the real boy was a football fan and not a poet, the judge took him to a football match, not a quiet moment in a judges’ lodgings – but the story is the same and it carries the same literary freight as any extended passage in a novel. In this case it is in literary terms a fake.

It can be argued, and McEwan would presumably argue, that all novelists research their subjects, take notes, interview people who have had experiences, and that in this he is no different from any other novelist. There is a difference, though. A serious writer will consider the information gained from research, digest and absorb it, think about it and wonder about it, seek a significance that is greater than that of mere plotting, look for any relevance that might exist on a symbolic or unconscious level, then write it from the heart. Ian McEwan does none of this: he copies down a story, fiddles around with names and a few details, then presents it as his own, written from the head. (There is a back-page acknowledgement to the real judge, so that’s OK then. I wonder if the learned judge realizes McEwan made a similar back-page acknowledgement in Atonement, to Lucilla Andrews?)

Ian McEwan is routinely described as Britain’s leading contemporary novelist. Could that possibly be true?

The Children Act by Ian McEwan. Jonathan Cape, 2014, 213pp, ISBN: 978-0-224-10199-8, £16.99

Cheltenham Literary Festival

I shall be appearing next weekend (Saturday 4th October) at the Cheltenham Literary Festival, on a panel discussion about the ever-cheerful subject of dystopian fiction. With me will be Jane Rogers (who recently won the Arthur C. Clarke Award for her novel The Testament of Jessie Lamb; also longlisted for the Man Booker) and Ken MacLeod (whose novel Descent was published earlier this year and will be out in paperback in November). The discussion will be moderated by the multi-award winning critic Cheryl Morgan. Details of the event can be found here.

I have been brought in at fairly short notice as a replacement for Brian Aldiss, who is indisposed – one fervently hopes not too greatly indisposed. I also note that the panel was originally to be moderated by my colleague Adam Roberts, but for reasons unknown (to me) he has pulled out. I wonder if word reached him that I am currently reading his new novel, Bête? Surely not – it’s the best of his I’ve read. So far.