Author: chris

Thirstier Choppers (anag. 11, 6)

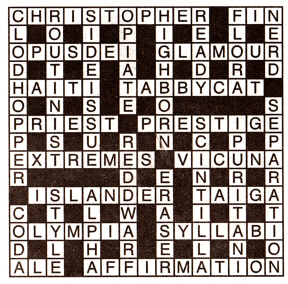

On Friday last week and without any warning, the Independent published the crossword below, no. 7919 in their excellent series, and compiled by ‘Phi’. I consider it to be an honour, in spite of 1 Down, which if I were feeling a bit paranoid I might interpret as a comment on my style. Even in the glory years of his reviewing, Rat Animism (anag. 6, 4) never quite got around to using this particular word when praising my novels, but exhausted every other synonym from that page of the thesaurus. 8 Down also has the potential for pejorative use, but that’s another one I don’t take too seriously.

The image should be more legible when enlarged, but if anyone would like a clearer copy drop me a line and I will send it as an attachment.

I’m grateful to Paul Dormer for spotting this, and to Dave Langford for passing on the news with enough time left for me to dash out and buy a copy of the paper before it became yesterday’s recycle stuff.

Answers are published here.

Coming to Brum

Rog Peyton has asked me to mention that I shall be giving a talk to Birmingham SF Group (Brum Group, as I’ve known it for nearly half a century) in a couple of weeks. Probably just as well that he reminded me, as those fifty years are starting to take their toll on memory.

DATE: Friday, 9th March. TIME: 8:00pm. In the conference room on the first floor of The Briar Rose Hotel, Bennetts Hill, which is off New Street. All welcome, including non-members. (Admission for non-members is £4.00. You don’t have to book — just turn up.)

Sam Youd

Today’s copy of the Guardian contains my obituary of Sam Youd, ‘John Christopher’, who died at the weekend. Like many obituaries, this was written to a tight deadline: I had less than four hours in which to research and write the piece, the research side of it being complicated by the fact that because of the heavy snow I was unable to get out of the house to consult more than the reference books I have on my shelf, and the internet.

One of the more irrelevant things I wanted to say (but lacked the space, so I suppose it was fortunate) was to remark on the weather. Sam Youd was born in a white-out blizzard in 1922; one of his best books was The World in Winter, published in a Penguin paperback during a terrible freeze in the early 1960s (I well remember buying it at an icy bookstall in Liverpool Street station); he died during the coldest weekend so far of this winter.

(Further text deleted.)

An Original Mind

I don’t know Adrian Hon, but he has an amazing way of thinking. His website Mssv has an analysis of The Islanders of such fierce intelligence that I gibbered in the cupboard under the stairs for half an hour afterwards. It’s an analysis, not a review, and whether he liked the book or not remains unsaid.

His chart of the islander themes is as close to a map of the Dream Archipelago as I’d allow. (I execrate the inclusion of maps in novels, as many people know.) But Hon’s chart is just that: a kind of flowchart of the psychic connections between islands and islanders. While not endorsing it entirely (I’m not certain I agree with it all) I’m happy to pass it on, partly for your pleasure of encountering an original thinker. While on his website, have a browse around. A lot of interesting stuff there.

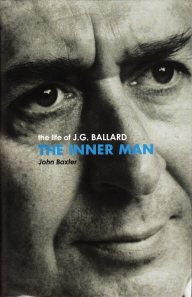

THE INNER MAN: The Life of J. G. Ballard – John Baxter (2011, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, £20.00; ISBN: 978 02978 6352 6)

Biographies of great writers, thrown together too soon after their deaths, tend towards the condition of a first draft of a life. The availability of living witnesses willing and eager to be interviewed, friends with scrapbooks and snapshots, even important locations as yet unchanged by time, seem to be too tempting to be ignored. Recent examples of this rush to be the first include Eric Jacobs’ biography of Kingsley Amis and Norman Sherry’s of Graham Greene. Both of these were inferior jobs.

Biographies of great writers, thrown together too soon after their deaths, tend towards the condition of a first draft of a life. The availability of living witnesses willing and eager to be interviewed, friends with scrapbooks and snapshots, even important locations as yet unchanged by time, seem to be too tempting to be ignored. Recent examples of this rush to be the first include Eric Jacobs’ biography of Kingsley Amis and Norman Sherry’s of Graham Greene. Both of these were inferior jobs.

Now here is John Baxter’s biography of J. G. Ballard, in print only two years after Ballard’s death. Baxter has previously written biographies of people like George Lucas and Robert De Niro, which I have not seen, but the Ballard biography is probably his first of a writer, and the first of a major author of international repute. The book has presumably not been authorized by anyone, certainly not by Ballard’s daughter, Beatrice, who has accused Baxter of hurrying this book out to make a quick buck, saying she had filled six pages with Baxter’s errors of fact.

Baxter claims to be Ballard’s literary contemporary, presumably as a justification for his rush to write this book. Technically, he’s correct: I well remember a number of stories by John Baxter in the Nova Publications New Worlds. At the end of 1962 I had discovered that J. G. Ballard was a frequent contributor to New Worlds so I started buying it regularly. What I soon realized was that with the exception of Ballard’s brilliant early work, and a few good stories by Brian Aldiss, the pages of New Worlds in the early 1960s were filled with mediocre work, mostly concerned with Earthmen solving puzzles on alien planets. Baxter’s stories were typical of this kind of thing, written in pedestrian prose and using familiar plots. The antithesis of Ballard’s stories, in fact. I feel a keen sense of anger at this faux modest attempt to present himself as some kind of equal. To be fair, Baxter’s writing style in this book is not as bad as his turgid early stories, and the uniquely interesting quality of Ballard’s work and life makes for a book that’s good enough. However, I’m left with the impression that if there is to be another biography it should be written by a writer of equal stature to Ballard himself, not a showbiz journalist who listens to gossip.

Gossip is the main weakness of Baxter’s book, because he falls foul of the temptation to rely too heavily on the memories of living witnesses. From evidence I have seen elsewhere, much of this book appears to have been heavily influenced by long interviews with Michael Moorcock. Baxter does acknowledge this: he refers to the ‘many hours’ in which Moorcock ‘recalled his memories of the man who, for three decades, was his closest friend’. Moorcock regularly describes himself as ‘Jimmy’s best friend’, as he has done in several long, rambling letters published in Pete Weston’s Relapse. Who can dare to question such an affectionate claim? As it happens I knew both men at this time, but did not see them together on any occasion. Whenever I saw Ballard alone he never once acted in the outrageous ways Baxter claims. On the contrary, he always appeared quiet, thoughtful and socially ill at ease. In his senior years, Moorcock has become a self-appointed chronicler of certain periods of the past, and in my view and direct experience (see my review of his blustering The Retreat from Liberty, published in New Statesman in 1983, in which I described how, unfortunately for Moorcock, I had happened to be present at one of the formative anecdotal experiences he claimed) he is an unreliable witness who filters every impression or experience through his own ego. One should weigh in the balance every word of his gossipy memoirs, which is something John Baxter clearly has not done.

Throughout the book, Baxter refers to Ballard as ‘Jim’, which I consider a presumption too far. First-name terms should be reserved to family and genuine friends. Baxter quotes freely from Ballard’s own utterances, presumably from articles or interviews, but does not note the source or give credit. Although there are at the back of the book a few pages of acknowledgements, and a long list of sources, none of these is cross-referenced to the quotes. How did the publisher allow Baxter to quote so much copyright material without direct acknowledgement or (apparently) permission? There is no Contents page. And how did the publisher approve the index, which not only contains a maze of passing references, but many subsidiary references without annotation? E.g. the index entry for New Worlds consists of thirty references by page number alone (and on investigation many of these turn out to be passing references). This lack of scholarly attention makes the book a poor reference work, even for an ordinary reader seeking information.

It is anyway a poor show. J. G. Ballard, now rightly recognized as one of the major 20th century writers, clearly deserves a substantial biography, but this is not it.

Dying is obviously an increasingly risky business. Get a few books published, or a few films made, and the gossips are out there, waiting for you with their unknown personal motives and their attempts to insinuate themselves into what little they can discover of your private life. I should hate to think that two years after my own death, my family would have to put up with a tabloid account written by a stranger, reporting what other people have said about me, and referring to me throughout as ‘Chris’.

J. G. Ballard biography

For Christmas I was given a copy of John Baxter’s biography of J. G. Ballard, and this is just a note to say that I have written a review of it, published below.

If anyone is interested in my reference to a certain review in New Statesman, I will try to find it in my ancient files and post it on this site, together with some accompanying material. The Ballard biography has brought home to me the importance of what weight we should place on verbal testimony, and its reliability or otherwise. The ancient incident described in NS was trivial and (for its subject) probably embarrassing, but when the same self-centred anecdotic rambling is used as evidence in the life of a great writer like Ballard, it’s time to get our priorities right. We have a responsibility to be true about these things.

The Stooge online

Some remarkably pleasant people in Hollywood are about to make a film based on something I’ve written. It’s the story of two stage magicians, and it tells what happens when …

Familiar stuff, perhaps, but this one is nothing to do with a certain blockbuster movie made a few years ago by Christopher Nolan. This one is also about stage magic, but in a completely different way. It’s based on a short story I wrote last year, under fairly unusual circumstances. It was commissioned by a well-known multinational bank based in London, and was published within one of their in-house training packages. My brief was identity theft, a fact that I report now with a straight face. I called the story “The Stooge”, and it concerns the kind of identity theft that banks don’t normally worry about. (They understood the metaphor, thank goodness, and they printed the story.)

After the book was printed I took another look at the story and thought how much I should like to see it performed on film. It’s short and sharp and its metaphorical theft of identity has a pleasing amount of naughtiness in it. On spec I wrote a script based on the story. It was intended to be no more than a short film, with a running time of less than about 20 minutes, so it would almost certainly never receive a trade showing — but even so. In past years I have served on film festival juries so I have a good working knowledge of the kind of stories that are entered in the short film competitions. I thought “The Stooge” would put up a good showing at festivals, if only I could find someone to film it.

Then I did. I suddenly found myself back in contact with an old friend in Los Angeles: Rogelio Fojo. For years Rogelio has had long-term plans to film one of my books, but has always been too busy to get around to it. Unexpectedly, on this occasion we both got our timing right. When he found out about “The Stooge”, a deal was done within a week.

Rogelio has since assembled a small team of experienced production professionals, and to my amazement they actually seem about to shoot the film. They are casting the main roles at the moment.

So here is a glimpse of what they are planning. It is a teaser pre-announcing the film called The Stooge, short and sweet (none of the naughty stuff), and is best seen at FULL SCREEN and with the volume turned up a little! Write to me c/o the Contact page on this site and let me know what you think?

Click here for Rogelio’s deft little Teaser.

And Another Earth

The problem with working in the slipstream is that many people misunderstand what you’re trying to do. This is also, of course, the greatest strength: you are free to do whatever you wish with slipstream without having to conform to expectations. Much slipstream is concerned with the fantastic, and this will sometimes add irritation to confusion, in the minds of those who expect genre clichés. A case in point is the critical reaction to Mike Cahill’s new film, Another Earth, which has been to a large extent hostile or uncomprehending.

The film bears a superficial similarity to Lars von Trier’s recent masterpiece, Melancholia, which for me was the best and greatest film I saw in 2011. In both films a previously undetected planet moves into the same planetary space as Earth. In Melancholia the outcome is depicted in the first few moments of the film: a visual prologue of shocking beauty and intensity – in Another Earth the new presence is of an altogether more subtle kind. A duplicate Earth, complete with attendant Moon, hovers in the sky. It has the same appearance: a blue-green sphere with swirling clouds, and a glimpse of the Horn of Africa.

It does nothing. It comes no closer, presents no apparent threat, sends no messages. When radio contact is eventually made it seems that Earth 2 (as the people on our world call it) is identical in every way. Synchronicity is all. The people of that world call their planet Earth, and have even dubbed our world Earth 2. What is it? A previously hidden and unsuspected world from the far side of the Sun (which is the irrelevant explanation offered by Melancholia)? A coincidence? A visual metaphor? An illusion? A glimpse into a parallel dimension? No matter – there it is.

And there is the fantastic element laid out, and is full of slipstream traps. Those who regularly enjoy a sneer at the trappings of science fiction film (sci-fi, as they call it) will wait for the weapons to be armed, the rockets to be launched, the robots to appear, the violent war to begin. They are going to be disappointed, and so will be the fans of that kind of stuff, if they go looking for it. Certainly, many of the film critics wrote reviews that veered between bafflement and hostility — presumably they had geared themselves up for a good and thoroughly enjoyable kicking of another sci-fi blockbuster.

The real story of Another Earth is an altogether quieter one and it occupies roughly 95% of the film. A young woman, Rhoda, celebrates her scholarship to MIT, where she plans to study astrophysics. She celebrates too hard and unwisely drives herself home. She hears a radio announcement of the mysterious appearance of the other planet, squints up drunkenly into the night sky to see the emerging blue shape, and collides head-on with another car. Her life is changed forever, as are the lives of the young family in the second car. She serves a long prison sentence for her criminal act, and emerges shattered. The other Earth hovers bluely in the sky above her. She finds a job as a janitor in a local school. Eventually, she makes tentative contact with the only survivor from the other car and discovers another shattered life. A difficult and emotionally impaired relationship starts to form, based on guilt, sorrow and a need to seek forgiveness. The other Earth hovers bluely in the sky above them, synchronous, silent, portending nothing more than a duplication that cannot be shared. But then there is a hint that the synchronicity ended when that first radio contact was made: the mirror has a tiny crack.

The film was written by Mike Cahill and Brit Marling, two names new to me. Cahill also directed the film and did the photography. Brit Marling plays Rhoda. I am eager to see what they will do next. Another Earth is a brilliant, beautiful and thoughtful film, pure slipstream, deeply felt, completely original.

LINKS. My earlier review of Melancholia is on the “Recent” page of this site. Here are baffled and negative reviews of Another Earth from two critics who normally get things right: Philip French and Peter Bradshaw. On the other hand, Roger Ebert came good. Finally, here is Mike Cahill launching semi-incoherently into the familiar but unavailing explanation of slipstream to a world of deaf ears — his film is better.

The Aweakening

Last night to see The Awakening, a British film about a ghost. The best thing about it is the central performance by Rebecca Hall, an actor whose career I have followed with interest ever since her rather intense and original portrayal of Sarah, the put-upon wife in the 2006 film of The Prestige. (You can read more about The Prestige in a moment.) Hall is a beautiful young woman, with an intelligent look and an active and subtly interrogative use of her eyes, that makes everything she does distinctive and memorable. If she is not yet a major star she soon will be.

The film is respectably and professionally made, backed by BBC Films and StudioCanal, and it looks good: muted colour, appropriate use of shallow focus, a tremendous stately-home location (Manderston House, near Berwick).

The weaknesses in the film are many. Least of them, perhaps, is the use of loud bangs on the soundtrack whenever anything sudden occurs, including falling in and out of water! All that a sudden surprise can do to the audience is make everyone jump — it doesn’t create a sense of menace, or fear, or even excitement. It just makes you jump, and after the third or fourth time you can’t help feeling that you are being manipulated into a response rather than being drawn into it by the excellence of the story, the acting or the writing.

Excellence is in short supply in The Awakening. The script is minimalist. The schoolboys who are at the centre of the story (the death of one of them after allegedly seeing a ghost traumatizes the others, and this is the event that initiates the main story) are treated as a bunch of diminutive extras in Eton collars and 1920s’ haircuts. We know nothing about any of them, and can barely tell them apart. They soon depart for half-term hols, leaving behind one of their number, who the film-makers apparently did not realize then obviously becomes Suspect No. 1. Such dialogue that exists between adults is cursory and plot-motivated. There are directorial touches that briefly suggest a greater depth in the characters (in particular, the briefly seen sadist, McNair), but the rest are shallow. Dominic West as a WW1 veteran with a limp, a stammer and a horrid bubo growing on his thigh, is merely adequate in an underwritten part. Imelda Staunton plays the school’s matron-cum-housekeeper, who exists inside a swarm of mumsy clichés, so that the moment she appears you know she is not at all what she wants us to think she is. Even the part played by Rebecca Hall is so underwritten that much of the film’s action depends on Ms Hall running around a lot in slightly dishevelled clothes, breathing stertorously and shouting in fear and/or anger. In addition, the dramatic integrity of her part depends entirely on our suspending disbelief that what happened to her as a child has been TOTALLY forgotten.

The script (co-written by Stephen Volk and director Nick Kirby) is not just minimalist, it’s extremely derivative. All the way through you keep being reminded of other films. At the start of the main story, for instance, there is a picturesquely photographed steam-train journey through lovely countryside, and you think in a bored way of Harry Potter. The great grey mansion where most of the story is set simply reminds you of a hundred other period films made in country estates, and you know that the catering tent, production vans and the spare bits of camera and lighting equipment are parked out of sight on the other side of the house. There is what seems at first an effective use of a dolls-house reproduction of the big house, which apparently contains tableaux of key events in the story, and then you remember the much less explicable, and therefore more sinister, scale miniature building in The Shining (1980). There are, incidentally, many more small details to remind you of The Shining. The overall approach to the visibility/invisibility of the dead is an unashamed lift from M. Night Shyamalan’s much over-rated The Sixth Sense (1999). So it goes.

Most of all, though, the film reminded me of the 2007 Spanish/Mexican film, directed by Juan Antonio Bayona, The Orphanage. Both films deal with a beautiful young woman going to or returning to a large country house, now in up-dated use (a school, an orphanage). Both films assume that small children are inherently sinister or frightening. Both have scenes of horror in which old mysteries are apparently re-enacted. Both depend on the reality of ghosts. And both include the logic-defying scene in which the central character discovers a previously unknown flight of steps, leading down into a dark and gloomy cellar where many horrible things seem likely to be lurking. Logic suggests that in the state of fright being endured by the young woman, just about the last thing on Earth that she is likely to do is start going down those steps while the menacing music rises around her.

And speaking of derivative, I’d like to record that pp. 62-66 of the first edition of my novel The Prestige (1995), and pp. 54-58 of the Gollancz Masterworks edition of the same book (2010), contain a detailed description of a fraudulent spiritualist meeting, where an elderly and recently bereaved lady is duped into believing that she can be put back in touch with her dear departed loved one. The fraud is violently exposed: the heavy blind keeping out the daylight is roughly pulled aside, the magician’s cheap tricks are sensationally exposed as the charlatanry they are. This scene was for some reason never used in Christopher Nolan’s film adaptation of the novel, but it plays a prominent part in the story of the novel. And it does, funnily enough, play a prominent part in The Awakening. It comes first in the film and is the scene by which the Rebecca Hall character’s deep scientific scepticism about ghosts is illustrated. Such exposées of spiritualist fraud are of course nothing new: Harry Houdini quite often broke into fake séances, and a couple of years ago Derren Brown was attempting something similar on his Channel 4 programme. However, I still felt that it was a reminder too far. It revealed this film’s unoriginal approach both to the subject of ghosts, and, much more seriously, to the making of film. Rebecca Hall deserves more original material to work in. She was good in The Prestige — pity she had to do it twice.