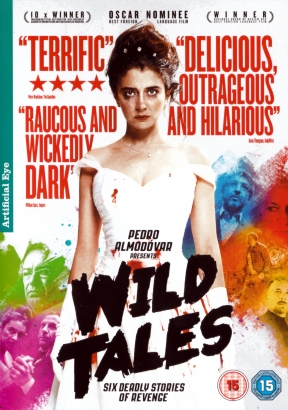

This is a recommendation to the Argentinian film Wild Tales (Relatos Salvajes), which we watched on DVD last weekend. It came out last year and has won prizes and awards at film festivals all over the world, although largely in South and Central America. It gained nominations for the Oscar and BAFTA awards (in the categories embarrassingly and chauvinistically called respectively “Foreign Language” and “Not in English”). It was also nominated for the Palme d’Or at the 2014 Cannes Film Festival.

Somehow, though, perhaps because it was thought to be “foreign”, it did not gain a theatrical release in the UK, and opened on a paltry four screens in the USA. Traditionally, English-speaking audiences are assumed by distributors to loathe sub-titled films. (It is exactly this kind of unthinking chauvinism that is ultimately behind the current controversy about actors in this year’s Academy Awards.) Whatever the reason, Wild Tales can be fairly said to have slipped through the Anglophone net. More fool us.

It is a wonderful film, one of the best made and most enjoyable I have seen in a long time. It is, though, difficult to describe and review, because of the form it takes. It is a portmanteau film, consisting of six individual short stories, without linking between them. In Wild Tales the stories have nothing in common beyond the theme: they are all about revenge.

It is a wonderful film, one of the best made and most enjoyable I have seen in a long time. It is, though, difficult to describe and review, because of the form it takes. It is a portmanteau film, consisting of six individual short stories, without linking between them. In Wild Tales the stories have nothing in common beyond the theme: they are all about revenge.

The wish for revenge is an intriguing subject, and here it is treated with flourish. Each of the stories is original and unusual, each is well told and skilfully filmed. The cast consists of actors who are not instantly familiar to British and American audiences, but are obviously well known in Argentina – perhaps the most familiar of the actors is Ricardo Darin, who was the lead in such (Argentinian) films as Nine Queens and The Secret in Their Eyes. But the ensemble acting is terrific throughout.

Each of the episodes is imaginatively constructed: there is an ingenious plot as well as the story, and the characters are properly and convincingly drawn. There are memorable images galore: you will never forget the astonishing image with which the first story ends, but it’s not a film of cinematic trickery. The concluding story, for example, is based entirely on character and good writing, and leads up to a most satisfactory and surprising ending.

Wild Tales was produced by Pedro Almodóvar, and was written and directed by Damián Szifrón. I hope Szifrón has a long and successful career ahead of him. I can hardly wait to watch his film again, and I suspect others will enjoy it as much.

However:

During the same weekend we saw a second film. This, oddly enough, had several features in common with Wild Tales. Much of it was filmed in Argentina, for instance. A lot of the dialogue has subtitles in English. It too is about revenge.

It was (perhaps not obviously from that brief summary) the recent blockbuster vehicle for Leonardo DiCaprio and Tom Hardy: The Revenant.

Whereas Wild Tales glories in superlative writing and storytelling, The Revenant is minimally scripted, has hardly any story at all and no plot to speak of. It is no more than an anecdote, padded out for two and a half hours. You will know the anecdote before you go into the cinema: DiCaprio is savaged by a bear, left for dead by his colleague Tom Hardy, and after he recovers he goes off in search of Hardy to exact revenge. There is nothing more to the film than that: apart from a lot of hanging around in cold weather, fabulous photography of cold weather, a dip in a freezing river, endless violence in cold weather, a lot of cruelty in the snow … and a quest for revenge.

Wild Tales was budgeted at $3 millions. The Revenant spent $135 millions. Wild Tales, as I said, opened on a mere handful of American screens. The Revenant opened on more than three thousand.

Wild Tales is the better film.