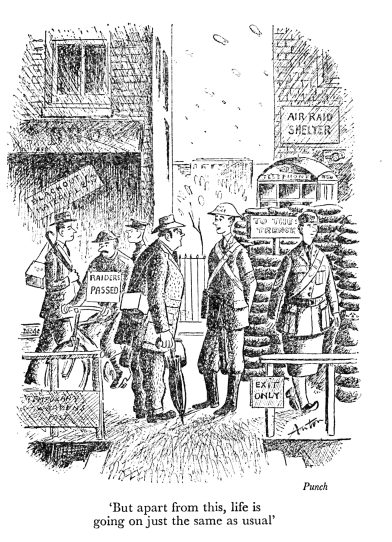

This was published in Punch in 1939. The artist was Antonia Yeoman:

author of The Prestige, The Separation and the story collection Episodes

This was published in Punch in 1939. The artist was Antonia Yeoman:

We do not use social media, so in modern terms we are fairly ‘silent’. A few kindly people have sent us emails enquiring how we are getting along in these unusual times and circumstances.

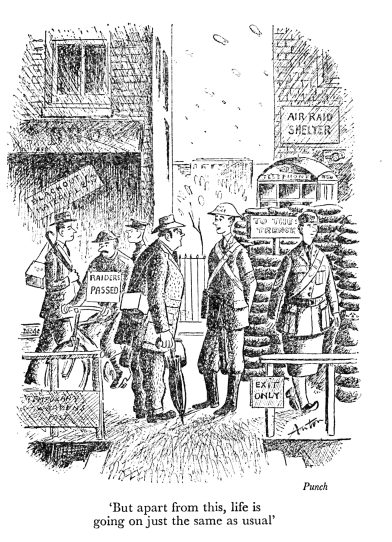

The answer is that Nina and I are both working on new novels, sitting alone in our respective studies, a state of affairs completely normal for us but which conveniently looks like self-isolation and in general accord with the government’s recommendations about social distancing. It’s a fast-changing situation, as everyone knows. There is as yet no trace of the coronavirus on the island, nor indeed anywhere in the rest of Argyll & Bute, a huge if not massively populated county. Because of the way these things work I assume the arrival of the dreaded thing is only a matter of when, not if.

We have decided, with immense regret, not to attend the Eastercon this year.

Looking at the rest of this blog I notice that the last time I wrote an entry here was in November last year. How time flies. That appreciative review of Amy Binns’ biography of John Wyndham produced only one response, and that was a howl of protest from someone else who had been working on the same subject but had failed either to finish it or find a publisher for it. I was held somehow responsible for their failure, and a stream of vindictive emails followed. I had never before invoked the power to redirect unwanted emails from an annoying correspondent into the spam folder, but once I did a blessed silence fell. It took until mid-February for the phrase ‘self-isolation’ to emerge, when I realized what I had done had a name.

All is therefore well here (for now), and although we are absorbed in what we are doing we are anxious to keep hearing from our friends about their own experiences in this alarming time.

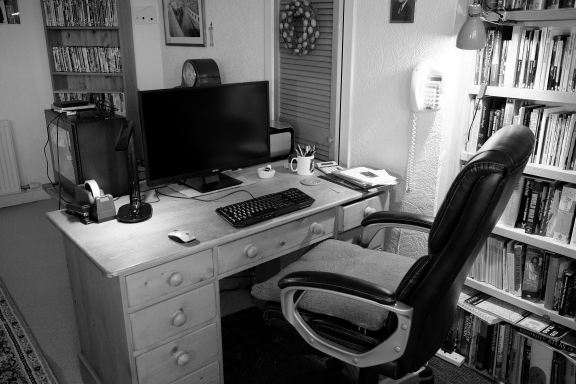

At last we have in Amy Binns’s new biography of John Wyndham a well-written and objectively researched book, half a century after his death in 1969. Wyndham was the first successful modern science fiction writer to emerge in Britain since H G Wells. His work, mostly written in the late 1940s or early 1950s, has acquired period charm, and some of the dialogue is middle class in tone and dated in style, but there is a hardness of vision, a satirical edge, a sense of the author’s regrets and sometimes amusement about the follies of the world at large.

At last we have in Amy Binns’s new biography of John Wyndham a well-written and objectively researched book, half a century after his death in 1969. Wyndham was the first successful modern science fiction writer to emerge in Britain since H G Wells. His work, mostly written in the late 1940s or early 1950s, has acquired period charm, and some of the dialogue is middle class in tone and dated in style, but there is a hardness of vision, a satirical edge, a sense of the author’s regrets and sometimes amusement about the follies of the world at large.

His books and short stories are remarkable for their constant depiction of strong, decisive or capable women. His speculative ideas, although sometimes reworked from his own early stories or from the generality of the genre, were presented plausibly and with a nice sense of menace. For example, his second novel, The Kraken Wakes, created a genuine and growing feeling of mystery and unease while an invasion force went about a deliberate and unexplained process of destroying our planet.

Amy Binns’s excellent book, Hidden Wyndham, depicts the author as a shy, withdrawn and deeply private man. There are no shocking details to be excavated from the past, there is no scandal, no secret life, although a tinge of sadness hung around him. At first he had to deal with the effects of being born into a dysfunctional middle-class family, his mother a distant if loving presence, his father a ne’er-do-well lawyer who sponged constantly off his wife’s wealthy parents. As a young man Wyndham began a tentative writing career in the American pulp magazines, which was interrupted when the second world war began. After war service he returned to his writing and became unexpectedly a major publishing phenomenon.

When his first books were successful he became known to other science fiction writers in London, including Arthur C Clarke (then much less celebrated), William F Temple and John Christopher. Wyndham regularly attended their monthly meetings at the White Hart and Globe pubs, but they seem to have learned little or nothing about his life. Later he collaborated with them to launch the magazine New Worlds SF as a commercial venture, but he retained his privacy. He lived somewhere in London, but they had no idea where. When he signed the official papers as Chairman of the new company, his address was revealed to be at a members’ club they had never heard of. ‘Wyndham’ was a kind of pseudonym – his real name turned out to be John Wyndham Parkes Lucas Beynon Harris.

When in 1963 he announced that he had married a friend called Grace Wilson, with whom he had been close for more than two decades, the other writers were astonished: he had always seemed isolated, self-sufficient, closed off, a classic bachelor of choice. In fact, as we discover from the archive of his hundreds of letters written to Grace (many of them sent while he was serving in the Army after D-Day), theirs was a loving, intimate and trusting relationship. For most of that time they chose to present as just friends: they rented adjacent rooms in London’s Penn Club, a strictly run private club established by Quakers which would not condone extra-marital relationships. Because marriage, or even more the admission of an affair, would in those days have had a drastic impact on Grace’s professional career (she was a senior teacher at a girls’ school, and for years the main breadwinner of the two of them), they decided to stay unwed. John Wyndham himself was content not to formalize their relationship until late in life. Once married, he and Grace stayed happily together until Wyndham died. He was at ease for the rest of his life, and the books brought him substantial financial security.

The quality of his work takes the general form of a bell curve. His early contributions to American science fiction magazines were typical of the period and have become badly dated – many of them were reprinted in modern editions after his success, and are mainly of curiosity interest now. The war arrived and Wyndham had to stop writing. He became one of the generation of British writers whose careers were put on hold for several years: others include Elizabeth Bowen, William Sansom, Rex Warner, H E Bates, Graham Greene. The involuntary pause had a different impact on the work of each individual, but in Wyndham’s case it seems to have been the making of him. The Day of the Triffids (1951), the first book published as by John Wyndham, is skilfully told in a mature and readable style. His other three great novels followed: The Kraken Wakes (1953), The Chrysalids (1955) and The Midwich Cuckoos (1957).

But these four represent the peak, the upper limit of the bell curve. Four more novels followed, none of them at the same standard as his best. Trouble with Lichen (1960) was a social satire, a distinct lowering of temperature from the others. The Outward Urge (1959, published in collaboration with ‘Lucas Parkes’ as nonexistent science adviser) was another disappointment. The last novel to be published in his lifetime was Chocky (1968), which was an adult novel with a child as a main character. After his death, a novel he had been struggling with for several years was finally published. Web (1979) was a long way below par, something of which John Wyndham himself was almost certainly aware.

Forty years after Wyndham’s death, an unpublished novel called Plan for Chaos was found in his papers at University of Liverpool. After a university press hardcover appeared in 2009, Penguin later published it in paperback. (I was commissioned to write an Introduction to their edition.) For imagined commercial reasons Plan for Chaos had been aimed at the American market, but the attempts at American dialogue and slang were crude and unsuccessful through most of the opening chapters. The second half of the novel is much better, and the story of the Nazi scientists who escaped to South America, and aimed to take over the world in their flying saucers, at least has the familiar Wyndham ironic humour.

Interestingly, Plan for Chaos was written after The Day of the Triffids, but it is significantly less accomplished. In correspondence with Frederik Pohl, his American literary agent, Wyndham said he thought the Englishness of Triffids would make it difficult to sell in the States. He put the better novel aside while he wrote the much weaker book intended to replace it.

There is some evidence (noted by Dr Binns in her book) that Ira Levin and John Wyndham had corresponded, and that Levin was likely to have read Plan for Chaos in manuscript. His own novel, The Boys from Brazil (1976), has a remarkably similar plot in outline. One of his other novels, This Perfect Day (1970), contains a coded acknowledgement to Wyndham.

The mysteries of John Wyndham’s private life turn out to be trivial, and no one’s business but his own. To read his love letters to Grace feels intrusive, but they give a context to the body of his best work. He seemed diffident and aloof to some who met him, but Amy Binns reveals him as a decent and faithful man, a lover of the countryside and a gifted storyteller. His books have been continuously in print for nearly seventy years, an extraordinary achievement.

Hidden Wyndham — Life, Love, Letters by Amy Binns, Grace Judson Press, pp 288, £10.95. ISBN: 978-0-9927567-1-0

Here are the one hundred books I consider to be my ‘key’ titles. They are not intended as recommendations as such, although in many cases I would in fact recommend them. I imagine many of the works here will be already familiar to most people reading this. The uniqueness lies only in the totality, the existence of one title thought of as special in the context of all the others of similar specialness, memorable in a life full of fairly disorganized and impulsive reading.

I have read them all, and they remain permanently on my shelves, but I have not read all of them all the way through. (I have read closely only a handful of Shakespeare’s Sonnets, for one example.) In most cases the book as a whole has had an impact on me, but in at least two instances what I remember most profoundly is an image from a single sentence, and in one other case it was a painted illustration that moved me — I only identified the work the painting was based on many years later. But of course several are here because I have read and re-read them many times (Alice in Wonderland was a constant favourite throughout my early childhood).

Speaking of Shakespeare, I have seen Hamlet performed four or maybe five times, but I have never read the play as a text. I can recall few lines from it, and accurately quote none of it, but when I hear the words spoken I am filled with a happy recognition.

The books are in alphabetical order by author — this is a way of slightly covering my tracks. Putting them in chronological order would be difficult and only approximate anyway, and even then would be far too revealing of how easy it is to be sucked into a series of like books, one after the other. The most recently discovered author on this list is the Chilean writer Roberto Bolaño.

But alphabetization of the authors produces its own oddness. There is Enid Blyton cheek by jowl with J G Ballard. And George Orwell and Beatrix Potter lie next to each other, even though three decades separate them. (I’m not saying which one came first.)

This particular listomania was brought on by Nina Allan, who has published her own list and talked me into doing mine. The whole thing was ultimately provoked by the current BBC-TV series, 100 Novels that Shaped our World. I do not claim world-shaping impact on me from these titles, nor are all of them novels, but they form part of the silent context from which one views the world and reacts to it.

Three years ago, along with a lot of other people in Britain, I placed my vote in the European referendum. The next morning I woke up to discover that overnight I had been labelled a “Remainer”, and was informed that my vote was on the losing side and that I therefore no longer had a voice in what would happen as a result of the referendum. All that has continued to be true ever since.

Three years ago, along with a lot of other people in Britain, I placed my vote in the European referendum. The next morning I woke up to discover that overnight I had been labelled a “Remainer”, and was informed that my vote was on the losing side and that I therefore no longer had a voice in what would happen as a result of the referendum. All that has continued to be true ever since.

I voted to Remain for what I felt were uncontroversial reasons.

Firstly, in the last forty years or so I have travelled in more than half the European countries who make up the EU. Although none of the countries represents a perfect world, an ideal place, I grew to like the way European countries ran things. Social problems are everywhere but they appear to be dealt with more effectively, more humanely than here in the UK. From my personal perspective there was effective environmental legislation in place, the rights of workers seemed protected, and the arts were better supported. Going to a book fair in Spain, or a literary festival in France or Germany, is an eye-opening experience from a British point of view, and wipes away forever the conceit that the UK is one of the most literate, book-loving countries in the world.

Secondly, having worked in the UK court service for nearly two decades I have become thoroughly versed in the importance, subtlety and civilizing quality of the European Convention on Human Rights. Incorporated into UK law in 1998 it has had what I see as a profound and desirable effect, if largely unrecognized and sometimes misunderstood, on many aspects of daily life in this country.

Thirdly, I lived in the south coast town of Hastings for nearly a quarter of a century. When I moved in it was a seaside dump, with many closed businesses, deteriorating housing stock, a horrendous drug problem and a pretty view of the English Channel. The view never changed, but our partner countries on the other side of the Channel were feeding millions of euros in subsidies and grants into many derelict British towns, including Hastings. All through the time I lived there the town was being cleaned up, repaired, invested in. By the time I left in 2014 it had been transformed. Hastings has become an attractive, prosperous and interesting place, with many cultural and artistic activities. (Now that I am living in Scotland I am starting to find out what similar EU investment in the past has done to improve lives and the environment here. Scotland is already a mini-European country in outlook and effectiveness. NB to people in England: after a few years of moratorium Scotland has just placed a permanent ban on fracking.)

So in a mild way, I felt the EU to be in general a good thing. It never occurred to me that many other people would have the strongly antagonistic feelings about it appallingly revealed in the months that have followed the referendum.

The “Leave” campaign in 2016 was largely run by three secondrate Tory politicians (Boris Johnson, Michael Gove and Iain Duncan Smith). They were a front for a sinister cabal of secretive businessmen and political opportunists. Laws were broken, and lies were told. Lies were told every day, in fact, some of them so blatantly untrue that they have become a sort of stock-in-trade for comedians. (Mentioning £350 millions a week for the NHS still gets a cheap laugh every time.) The campaign they ran was emotive, it fudged detail, it avoided real issues, it appealed to people’s baser instincts about foreigners and immigrants and hospital waiting lists. Again, these tactics were so conspicuously dishonest that I assumed most people would have the sense to realize what was being said.

Interestingly, as the weak Tory government has tried in recent months to negotiate what they always call a “deal” (a horrible word made popular by Trump’s dishonest practices), it has become blazingly obvious that none of the real issues of leaving the EU, none of the serious problems, were ever mentioned by anyone in the Leave campaign. Does anyone remember the Leave campaign explaining how the problem of the Irish border would be solved?

So it is apparent that many people who voted to Leave were either gulled by the lies (or chose to ignore them after they were exposed), or they were not informed of the reality of what they were voting for. They followed their instincts instead.

The referendum was an opportunity to succumb to the temptation to push a sharp stick into the eyes of the Tory nobs who ran the country. (Not such a bad idea, in socialistic fact: David Cameron’s cabinet contained a majority of public school boys, and at least eleven millionaires.) It was a protest about foreign workers taking up jobs that should have been given to British people. It was a fear of being swamped by immigration. It was a complaint that operations for varicose veins, cataract implants, replacement hips (and treatment for more serious emergencies, like cancer, stroke, etc) were the subject of long delays. It was anger that the schools were crowded and underfunded, that doctors’ surgeries were crammed with freeloading foreigners, that jobs were hard to come by …

All these are genuine concerns, and many people feel disadvantaged by them. But the root cause is not the arrival of refugees from dysfunctional regimes abroad, or Polish workmen, or Bulgarian fruit-pickers, or the policy of freedom of movement, or the unpoliced borders that inadequately protect our island. The truth is that we have been suffering from weak governments dominated by businessmen and hedgefund operatives, short-sighted policies, endless restrictions in the name of “austerity”, and above all a thoroughgoing lack of awareness about what many ordinary people care about on a daily basis, and the problems they have.

In case this seems to be a one-sided tirade against the Tories, let me add that I consider the principal scoundrel responsible for the Brexit mess to be the leader of the Labour Party, Jeremy Corbyn. Where was the opposition during the referendum campaign? Who challenged the glib lies? Who raised the problem of the Irish border? Not Jeremy Corbyn, who apart from one self-evidently insincere little speech about supporting the Remain side, was all but invisible. His absence created the unfailing impression that the referendum was really just a squabble between two factions in the Conservative Party. Since the referendum, Corbyn’s endless vacillation and unconvincing announcements have only added to the ineffectiveness of this man. He is more responsible than Cameron, May or even Johnson for the mess we are in. There is a place reserved in Brexit hell for Jeremy Corbyn – I’d like to think of him spending eternity in a cell with Michael Gove and Iain Duncan Smith.

Today was planned to be the last day of our membership of the EU. Thankfully postponed yet again, it has become instead the first day of the General Election campaign. I have never voted Tory in my life, and in the past I worked as a campaign volunteer for the Labour Party. But should you sense even the whisper of a bat’s wing of temptation to vote for Corbyn’s party, I recommend you first to read Tom Bowyer’s biography of Corbyn, just so you know what you would be voting for.

There is only one solution to this mess. The best “deal” is the one we have. Referenda have no constitutional position in the UK. They are advisory only. The next government should swiftly consult the advice of the 2016 referendum, disagree with it, politely reject it, then revoke Article 50 and mend fences with our European friends and say sorry for all the botheration. Corbyn’s head on a stick might be enough to soothe their justifiable irritation with our otherwise green and pleasant land.

Further reading, if you can find a copy – Amazon.co.uk have a few copies at 50p each: Yea or Nay? – Referenda in the United Kingdom, by Stanley Alderson.

I see my last entry here was more than two months ago. There has been a period of delay, not at all my doing. Meanwhile, I have news of two or three public events in which I shall soon be taking part:

I shall be at Novacon 49, at the Nottingham Sherwood Hotel, from 8 – 10 November. I shall be accompanying my daughter Elizabeth Priest, currently famous all over America since the Wall Street Journal unironically reported that she had not only ironically stockpiled Nutella, mozzarella and lactose-free milk in case of Brexit, but had eaten her way through the lot as one Brexit postponement followed another. More interestingly, Lizzy has just signed up with Luna Press for three more novels in her Troutespond series.

On 14th November I will be at Waterstones in Notting Hill, London W11, where we will be discussing the life and works of Anna Kavan, the fascinating author of the novel Ice, as well as several more novels and collections. She is still, in spite of the best efforts of the likes of me, Brian Aldiss, Doris Lessing and her publishers Peter Owen, woefully underrated. From 7:00pm to 8:30pm — tickets £3.00 from the website linked here.

A week later, on 21st November, I shall be at Cardonald Library, taking part in Book Week Scotland. Admission: free. 6:30pm to 7:30pm. Cardonald Library is on the main road between Paisley and the centre of Glasgow, halfway along. There is a map on the website.

The composer John Hodgson has, with astonishing speed and dedication, written a suite of music based on my collection of stories, Episodes. It illustrates, or complements, the book.

Each of the eleven stories has its own composition – I have played the whole suite only once, so I am still absorbing. The entire album can be listened to on the SoundCloud website, here.

Hodgson has also written musical complements to books by Mark Morris and Jeff Noon. They can be heard on the same website.

Rogelio Fojo’s remarkable film of my short story ‘The Stooge’ has gained another festival screening, this one the Burbank International Film Festival, 4-8 September 2019. The story itself (the film tie-in, if you like, although it came first) appears in my new collection Episodes – see below. This will be on sale later this week.

Here is another still from the film:

This is my new hardcover from Gollancz, to my mind a well designed and handsome edition. It will be published on 11 July, available in bookstores … and of course may be ordered through Amazon and other online retailers.

Episodes is a collection of short stories with something extra. Each story has a Before and After, two short essays describing how the story came to be written, and what happened to it after that. The idea was to show how tangled the background to the appearance of a short story can sometimes be. For instance, ‘An Infinite Summer’ is a harmless story about innocent love, but it had a pretty aggravating time in the hands of a particular American editor. The full account of what happened to that story is here, and I believe that this is the first time the professional activities, or more accurately the unprofessional non-activities, of that egregious timewaster have been reported accurately in the world of general publishing.

Other stories have their own backgrounds of personal provenance. The elderly woman who arranged for branches of trees to be slung at my car. The bank which thought literature could be made into a staff training device. The weird coincidence of two tragic deaths in train stations: one in the story, the other for real. The previously undescribed horror of an alphabetized book collection.

Also published on 11 July is the paperback edition of my most recently published novel An American Story. For readers in the USA the only way to obtain copies is through internet retailers. Here is a link to amazon.co.uk, although I suspect amazon.com will also make it available. It is still the case that this story of a broken love affair, and the untrue story that obfuscates it, is deemed unsuitable for American readers. (However the novel has done OK in Russia, France, the UK, etc.) Distribution in the US of the British edition is likely to follow in due course, but I know not when.

I have not written much here in recent weeks. I have been working on a new novel, and today I sent it in to Robert Kirby, my agent. Uniquely, in my experience, I had a period of more or less six months without interruptions, and I made the most of it.

I was at Utopiales, in Nantes, at the beginning of November, but returned feeling worn out and over-extended. Too much travel, and a heavy cold contracted because of Easyjet’s tight-fisted habit of overcrowding their unforgivably minimalist cabins, laid me flat during much of the rest of the month. I rose from the bed at the beginning of December, and almost immediately began work on the novel. I was refreshed, renewed, and had at last stopped coughing.

Amazingly, to me if not to anyone else, I had completed the first draft before the end of February. I began the second draft the next day, and that was completed mid-May. (The sole interruption during that period was Easter weekend, when I was at Ytterbium in London.) For the last couple of weeks I have been doing last minute corrections and amendments, but today it is all done. Overall, writing the novel was a happy experience. This morning the sun is shining, the Firth is mirror-calm, the ferries are sailing to and fro. I am free.

The new novel is unlike any of my previous novels, and stands as a sort of antidote to what happened to the first edition of An American Story. (We suspend judgement on what the trade will do with the paperback of that, due next month, along with a new hardcover collection of stories, Episodes.) No publishing arrangement has yet been made for the new book.

I shall be at Cymera, a book festival in Edinburgh, this coming weekend. Details: Sunday 9th June, 4.45 p.m, in Upper Hall, The Pleasance, 60 Pleasance, Edinburgh. EH8 9TJ. Details of my gig are here. Details of the Cymera festival are here.

On Friday 12th July, Nina Allan and I will be at BSFG (Brumgroup): 7:30 p.m. for 8:00 p.m., First Floor, The Briar Rose Hotel, Bennetts Hill, Birmingham. More details of BSFG here.