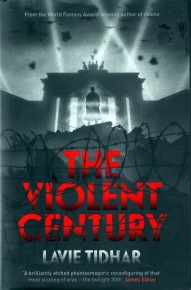

Lavie Tidhar’s new novel The Violent Century has been packaged as a general novel, with no hint of what is inside. The cover, with its silhouette of Brandenburger Tor, and anti-aircraft shells bursting in the sky around looming bombers, suggests a WW2 novel. The blurb refers coyly to a gunshot, a body in a river, a plane crashing into a skyscraper … and a perfect summer’s day. That the publishers (Hodder & Stoughton, £18.99) are not letting on about something is manifest. However, I suspect most early readers of this novel, at least as long as it remains in hard covers, will have come to it because they admired Tidhar’s earlier novel, Osama. I certainly did. Those readers, like me, will not be misdirected by the cover, as our appetites for what this young writer might do after the brilliant, if slightly flawed, Osama were well whetted.

It turns out that the publishers’ guilty secret is that the novel is about superheroes. The Violent Century presents an alternative view of the history of the 20th century, as seen by a group of Übermenschen, or super-men. But these are not Nietzsche’s Übermenschen – they are the sort of superhero characters you find in comic books. The comics of course partly originated from the Nietzschean concept of men and women who should aim to rise ‘above or beyond’ the normal – but they were no longer super-men in that philosophical sense. The comic book writers created the popular idiom, but the Nazis were there two or three years before them. Both took the concept literally and then dumbed it down.

It turns out that the publishers’ guilty secret is that the novel is about superheroes. The Violent Century presents an alternative view of the history of the 20th century, as seen by a group of Übermenschen, or super-men. But these are not Nietzsche’s Übermenschen – they are the sort of superhero characters you find in comic books. The comics of course partly originated from the Nietzschean concept of men and women who should aim to rise ‘above or beyond’ the normal – but they were no longer super-men in that philosophical sense. The comic book writers created the popular idiom, but the Nazis were there two or three years before them. Both took the concept literally and then dumbed it down.

Nietzsche of course never intended the concept to mean a body-builder in a brightly coloured skin-tight costume who can halt a hurtling train with his hands, and neither did he mean the breeding of a genetically managed master race. This interpretative misnomer provides much of the plot tension of The Violent Century, as Tidhar’s small group of super-men witness or observe or marginally take part in various violent episodes of the Nazi era.

The central character, Henry Fogg, has the ‘super power’ of creating a blinding miasma of mist or smoke or fog, with which he can confuse, obfuscate, escape, etc. His friend and would-be beau, Oblivion, has the power when sufficiently provoked to, well, cast into oblivion those who threaten him. Other super-characters appear: a Whirlwind, a Tank, a Tigerman, a Machentraum, and so on. The plot largely turns on the quest to find the Übermensch who has, so to speak, gone over to the Nazis, one Schneesturm, as well as Fogg’s more personal quest to be reunited with Klara, after a romantic and sexual interlude with her. Klara is the daughter of Vomacht, the scientist who is said to have developed the process by which these people were ‘changed’, and she was in fact the very first to be changed.

The novel concentrates on Nazi atrocities during WW2, although there is a postscript set in the ruins of Berlin in 1946, and a brief incident in the Indochinese wars during the 1960s, and an even more fleeting reference to 9/11. Because of this over-emphasis on one relatively short period of history the main events of the novel really constitute a violent decade, rather than a century. An author should not be held ransom to his title, but this one does suggest a deeper engagement with history than is in fact the case.

Fogg and Oblivion mostly observe incidents which are well known to history: the D-Day landings, the military occupation of Minsk by the Nazis, the hideous experiments of Josef Mengele in Auschwitz, and so on. As observers they are inert. What is the point of these superheroes merely looking and commenting? When they do involve themselves, the brief action is almost always on the fringes, the historical outcome not being affected in any way. The implication is that superheroes should not act effectively. Wouldn’t that be contrary to the whole idea of being a superhero?

It is unclear what we are intended to learn about history that we did not know before. Fiction provides a mirror to reality, a way of testing what we believe to be known, and we can presume that this was the sort of instinct that lay behind writing the novel. In an afterword Tidhar sets out the reality behind his fiction, but it merely confirms the facts that most people are already familiar with. What he does not address is that because his characters are inert his take on history can never be more than superficial. The novel is also partial. By concentrating on the 12-year period of Nazi rule in Germany it says nothing about other events that were as bad, or worse: the Stalin purges, the killing fields of Cambodia, the massacres in Rwanda, the use of nerve gas by Saddam Hussein, the fire-bombing of Hamburg, Dresden and Pforzheim, the nuking of Nagasaki. And there is another kind of partiality: the novel concerns itself for instance with the division of Germany and the building of the Berlin Wall, but is silent on the equally brutalist West Bank Barrier. Tidhar’s history is more or less bunk.

In essence, the novel is told on two levels: a sort of debriefing in the present day by a George Smiley figure called the Old Man, who takes a paternal interest in his young heroes, with the main narrative consisting of flashbacks to the incidents themselves. The conversations that take place in the Old Man’s office throughout the book are banal, chatty and inconclusive, so really serve as a sort of narrative continuo, quiet bits that link the exciting bits. But the main passages, the flashbacks, are also curiously uninvolving.

All of this raises the connected problem of using superhero characters in a serious novel.

Seriousness is Tidhar’s own agenda. Attempts at it spill from every page of The Violent Century, with the same sort of interest in psychological realism, human urges, emotional complexity, etc., that has been the inspiration of the recent Batman movies directed by Christopher Nolan. Superheroes have become big business, at least in film, and their presence is starting to be taken for granted, a sort of donnée that by sheer persistence is no longer questioned.

In this, superheroes are similar to what has happened to zombies, a current infatuation of many writers, readers and publishers. Familiarity does not eradicate the essential silliness of such trivial notions. There is not a crumb of scientific possibility (or, for that matter, of imaginative viability) for reanimated corpses wandering down apocalyptic streets – or, to keep to the subject in hand, neither is there for adapted humans who can breathe underwater, kill with a well-aimed spit, put back time by a few minutes, and so on. The superhero comics celebrated by Tidhar in this novel are by design simplistic. Problems and crises are usually of a single issue, and are resolved in their pages in an emphatic and single-minded way. Comic book apologists often point out that the characters’ self-doubts, foibles, weaknesses and heroic shortcomings are part of the tradition too, but such sub-plot materials are resolved only by sub-plot devices. Both zombies and superheroes have become so familiar and degraded that they are clearly in what Joanna Russ described as the Decadent stage of worn-out genre materials.

The tropes of superheroes are fanciful notions, not ideas with metaphorical depth, and any attempt to dignify them with a serious purpose is to try to make a silk purse out of the sow’s ear of narrative material that has been debased for years by shallow and exploitative work.

Finally, Tidhar’s chosen style of writing cannot be ignored. Most of the narrative is told in short, unparsed sentences. Here is a typical short section from close to the beginning of the novel:

Walks away, towards the building. Fogg follows. Nondescript building. Can’t really tell what, if anything, is inside. Could be a bank. Could be a warehouse. Could be anything.

They go around to the side of the building. A narrow alleyway. A door set in the wall. No handle. They stop in front of it. Stare. [p.17]

This is lazy, evasive writing. It is lazy because no trouble is required to type one expressionist ejaculation after another. It is evasive because it uses what amounts to bullet points to establish every image, and does not take the trouble to find the best arrangement of words to convey the message. It seems to seek to recapture the quality of narrative panels in the comics, the voice-balloons which accompany almost every action, no matter how violent. It also smacks of an attempt to reproduce the terse, effective noir style of thriller writers like Hammett or Chandler. Formal prose (which Tidhar employed well in Osama, and which as a matter of fact both Hammett and Chandler excelled in) has not been developed as a sort of posh mannerism favoured only by literary writers. English prose can be subtle, exciting, descriptive, rhythmic, mood-inducing, beautiful, shocking. Good prose is a required art, and to scatter short sentences in undigested lumps throughout a novel is a wicked thing to do. It is a type of writing familiar to anyone who has read a screenplay: the words are deployed as shorthand, a simple code to convey images and ideas without distracting the presumably busy producer or director. Film scripts are never read for style – they are seen as a halfway house before the storyboard is drafted. Film people only feel safe with pictures.

In fact, Tidhar’s style is not half bad when he can be bothered to write properly. There is a short sequence in the middle of the novel, a lyrical passage describing Fogg’s affair with Klara, where the ugly machine-gun scatter of words temporarily ceases. Here he writes plain descriptive language, and although at times it teeters on the edge of being something that could be nominated for the annual Bad Sex Award, it is written in a way the reader will comprehend and so it becomes one of the best scenes in the novel.

Nor is the lack of descriptive prose the only thing that’s wrong. For some reason, Tidhar has opted in this novel to abandon the conventions of dialogue, and sets out all the characters’ words so that they blend with the rest and are indistinguishable from it. Maybe some will see this as a dramatic and even daring innovation, but it is a gimmick many have tried before and it is always tiresome for the reader. Tidhar compounds it by sometimes leaving off question marks, and although his solecisms are not as bad as those of many of his colleagues he should be more careful of details.

A fug of smoke cannot ‘crescendo’; the word ‘oblivion’ means the state of being forgotten or disregarded, and is not a synonym for ‘annihilation’; similarly, there is no such word as ‘obliviating’; air does not condense out of mouths in cold weather, but breath does (Tidhar gets this right later, so he knows the difference); someone who has a hole blown out of his head is described as ‘very dead’, which is presumably much more dead than just dead; ‘“We don’t age,” the Old Man said’, which suggests he must have been born old; colours don’t ‘leech’ away.

A copy editor, or Tidhar himself in a final draft, should have corrected all of these. They weren’t corrected, though, and as Tidhar is clearly being treated now as a high quality writer, the question of his style is important.

In spite of all this, Lavie Tidhar is a gifted writer. When he puts himself out he writes effectively and well, but in this novel those occasions are few and far between. He researches thoroughly and displays discernment over what he uses. He clearly has an original mind. His vocabulary, when he chooses to deploy it properly, is good and varied. I hope he will grow to see The Violent Century as an aberration, an error of judgement. Osama quite rightly drew attention to Tidhar’s real qualities and genuine promise as a novelist of the fantastic, but this is not the novel he should have written to consolidate his reputation. It is boring and shallow, clumsily written and not at all pleasant to read. It required a conscious struggle to stay interested enough to get to the end.